The first time you see an Egungun, you don’t know what you’re looking at.

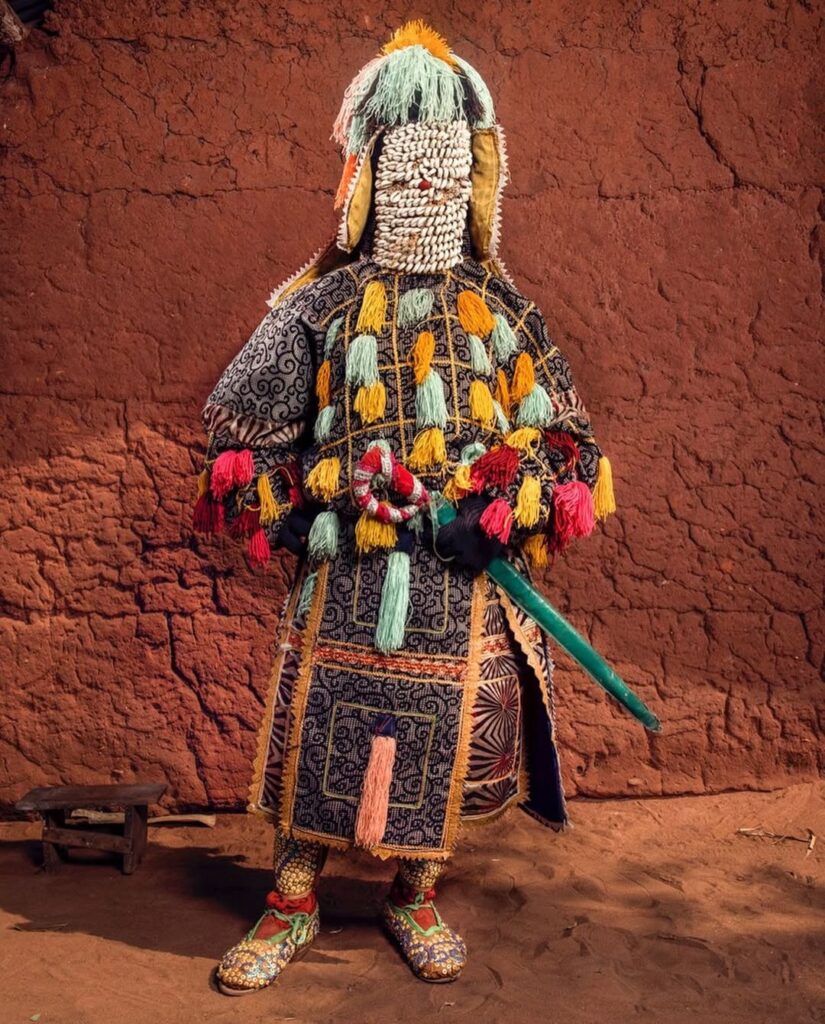

Something comes out of the trees. Maybe ten feet tall, covered in fabric, and moving in a way that doesn’t look right. There’s a person inside, you assume, but you can’t see any part of them. The cloth is thick with embroidery, cowrie shells, scraps of older material. It spins and the panels fly out and there’s a sound, this rushing noise. The Yoruba say that’s the voice of the dead.

You keep trying to spot the guy inside. You can’t. That’s the point.

Outside the communities that practice it, Egungun gets misread constantly. Online, the masquerades become clips — “costumes,” “creatures,” “characters.” People aren’t being malicious; it’s just the internet doing what it does, flattening everything into content. But Egungun predates the vocabulary being thrown at it, and exists for reasons that don’t fit in a caption.

The tradition goes back further than anyone can document. Southwestern Nigeria, Benin, Togo, cities and villages that don’t show up on most maps. When the season is right and the rituals have been handled, the masquerades come out. The logic is simple and non-negotiable: the dead don’t leave. They transition. And every so often, they come back to see what the living have been up to.

Apparently they have opinions. Egungun can bless you and Egungun can call you out. They can praise a woman who’s been good to her neighbors, or publicly shame a man who’s been cheating his brother. They say things that would cause serious problems if a living person said them. But you don’t argue with your dead grandfather. You just don’t.

As one priest reportedly put it: “The masquerade knows what the village knows. It just doesn’t have to be polite about it.”

These things take years to build. Sometimes generations.

Rights to a specific Egungun pass through families like land or titles. A son inherits his father’s masquerade and adds to it: new fabric, new charms, meanings stitched into hems that outsiders won’t be told about, some of it protective, some of it decorative, some of it nobody’s business including yours. The full assembly can weigh a lot. I’ve heard thirty pounds, I’ve heard more. Learning to move in it without tripping, to spin without tangling yourself, to become something other than yourself while also not passing out from the heat, that training starts young, and not everyone makes it through.

Everything has to be covered. A visible hand, a flash of ankle, and the whole thing falls apart. The human has to vanish completely for the ancestor to arrive. Not symbolically. Actually.

At some point in most festivals, the Egungun spins fast enough that the fabric lifts into a full circle of color. Looks great in photos. But what the locals are listening for is something else: the sound of the panels rushing against each other. Families say they can tell which ancestor is present by the specific noise the cloth makes. I don’t know if that’s true. I also don’t know that it isn’t.

It’s hard to describe these festivals without making them sound like theater, which misses something essential. There are drums, obviously. Rhythms learned over years, signaling what’s happening and who’s coming out. Priests handle things beforehand that visitors don’t see. When the Egungun finally appears, young men flank it — keeping the crowd back, managing the logistics of someone wearing thirty pounds of fabric who can barely see.

People watch, pray, ask for things and move fast when the ancestor lunges toward them. Not because it’s fun and scary, but because getting hit by an Egungun, even by accident, is something you’ll be explaining to your family for a long time.

What’s in the air isn’t only spectacle. There’s fear, obviously. Joy. Something harder to name — a feeling that the normal rules are suspended. For a few hours, everyone’s operating on different assumptions. The dead are here and they have things to say. The correct response is respect.

How did this survive the twentieth century? Colonial administrators hated it. Missionaries called it devil worship. Post-independence governments weren’t always enthusiastic about traditions that operated outside their control.

And yet, the groves stayed. The families kept their rights. The drums kept their patterns. Part of it is Yoruba stubbornness — this talent for preserving what matters while appearing to go along with whoever’s in charge at the moment. But mostly it’s that Egungun does something nothing else does. Churches offer salvation. Governments offer services. The masquerade offers the dead, in person, walking through town and holding people accountable.

Turns out people want that. Enough to keep it going through colonialism, independence, urbanization, iPhones, all of it.

Lately, Egungun has found its way onto the internet. A clip of a spinning figure goes around on TikTok. Someone reposts it on Instagram: “fashion inspiration.” Someone in the comments asks where to order one. Ripped out of context, it becomes content. No priests, no families, no ritual, no belief system. A vibe. A meme.

But the Yoruba aren’t confused about what they’re doing. They’re not performing for an audience. They’re talking to their dead.

If you’ve been to one of these, what stays with you isn’t how it looked. It’s the logic underneath. The idea that the dead don’t just go away. That they’re still paying attention. That there’s a connection between the living and the dead, and someone has to keep it going.

It’s demanding. It asks you to show up. To be seen by people who aren’t alive anymore.

You don’t have to believe it. But it’s hard to argue with the idea that the dead deserve more than being forgotten.