When Beyoncé appeared in Black Is King, her face veiled in a mask of cowrie shells, the world saw ornament. Africans saw memory. These glossy shells once banned, once branded “demonic” had returned to the global stage, shimmering with pride. Behind them stood Lafalaise Dion, the Ivorian designer who has become the “Queen of Cowries,” reclaiming a symbol that carried empires and endured erasure.

Long before the dollar or the euro, cowrie shells flowed through the arteries of African trade. From Timbuktu to Benin City, they bought gold, salt, and textiles; they signaled wealth and crowned kings. In the 1850s, explorer Heinrich Barth observed that 25 shells could feed a family, while a horse cost 20,000. At their peak, half a million shells might move in a single caravan deal. But abundance turned to exploitation. By the 18th century, European traders shipped billions of shells from ports in Amsterdam and Liverpool, flooding West Africa. Cowries became currency in the transatlantic slave trade: a human life could be priced at 30,000 shells. Inflation soared, economies buckled, and colonial authorities eventually outlawed them, enforcing francs and pounds instead. Still, in markets from rural Nigeria to northern Ghana, cowries continued to circulate well into the 20th century. Ghana’s own “cedi” still carries their name.

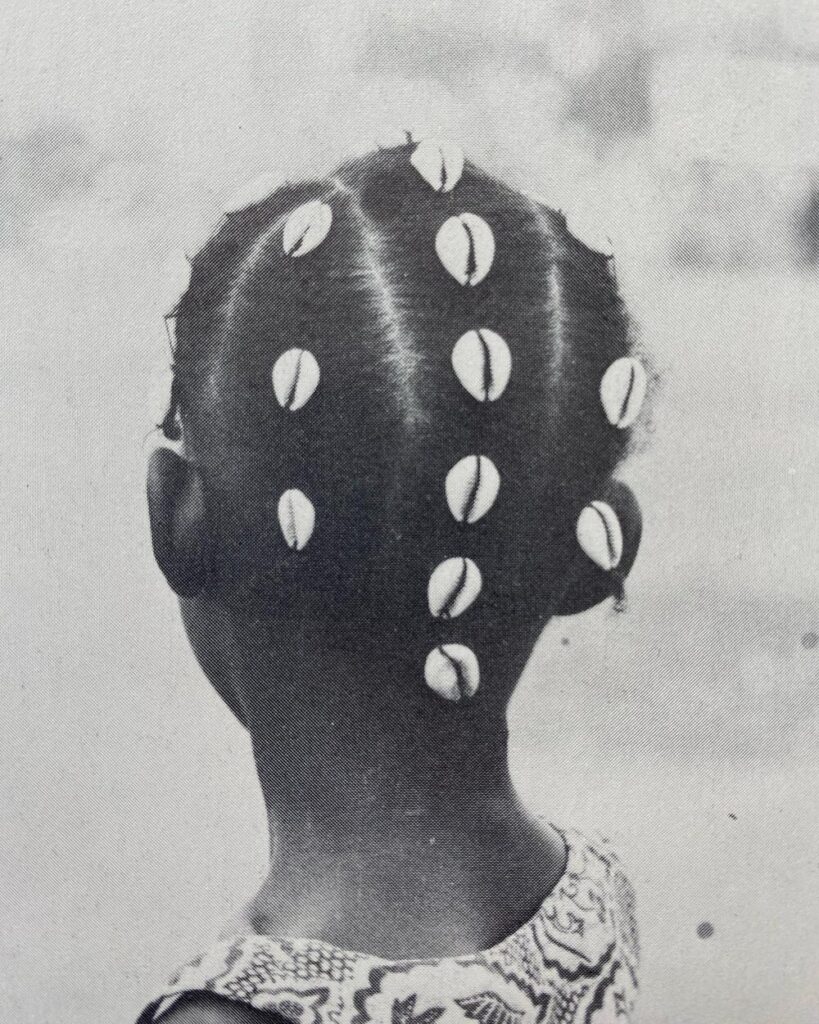

To Africans, cowries were never just money. Their womb-like curve linked them to fertility; their polished surface to protection. Among the Yoruba, they were the “mouth of the orishas,” used in divination rituals where 16 shells spoke for the ancestors. Dogon fortune-tellers and Vodun priests cast them to purify and guide. Sewn into garments and headdresses, they shielded wearers from harm and announced power. Literature caught their resonance too. In Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart, cowries mark wealth and hierarchy. In rituals and storytelling, they bridged the earthly and the divine — an inheritance colonizers could not erase.

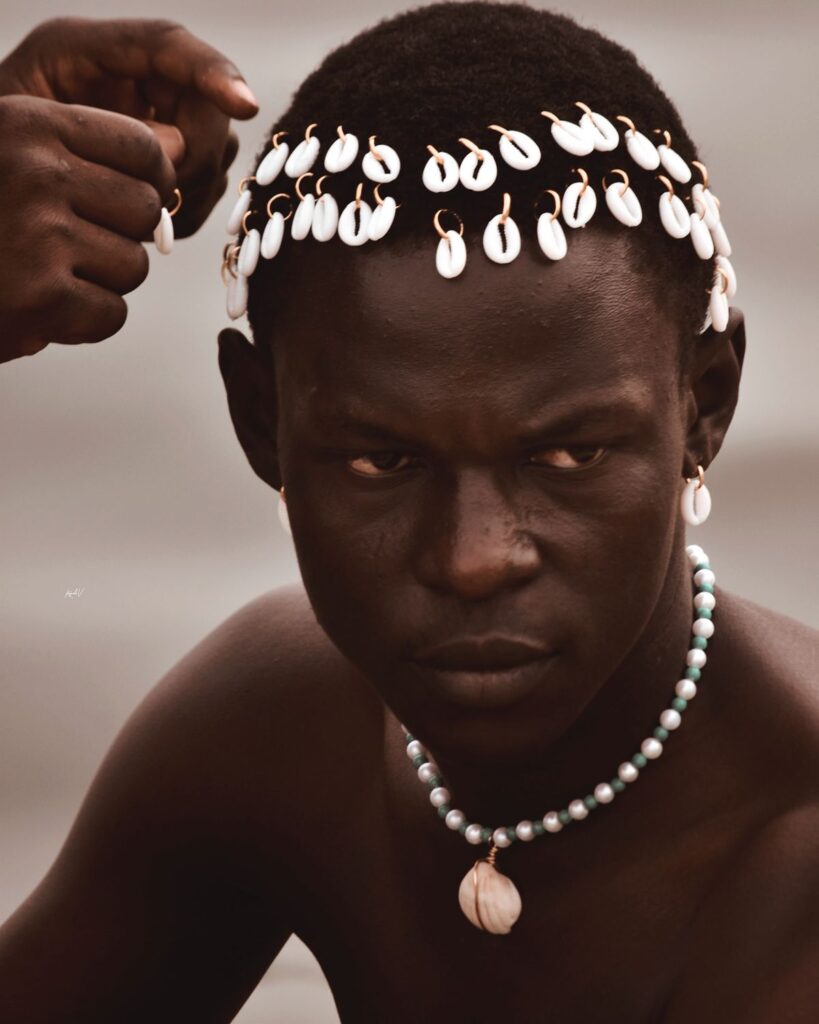

This inheritance is what Lafalaise Dion channels. Born in Man, Côte d’Ivoire, and rooted in Dan (Yacouba) culture, she grew up seeing Tématé dancers crowned in shells. Yet colonial stigma lingered: cowries were once dismissed as “demonic.” At Ghana’s Chale Wote Street Art Festival in 2018, Dion wore a cowrie crown in defiance. That moment sparked a revolution in her craft. A year later, Beyoncé wore Dion’s “Lagbaja” mask, a Yoruba-inspired piece meaning “unknown man” in the Spirit video for The Lion King: The Gift. In Black Is King, more than 20 of Dion’s creations transformed cowries into anthems of African beauty and resilience. Stylist Zerina Akers called them a “nod to opulence and the past,” a signal that history had become fashion’s future.

Dion’s work, shown with Acne Studios at Paris Fashion Week and sold globally through Afrikrea and Etsy, is crafted by Ivorian artisans in two to four days, each piece hand-threaded with sustainably sourced shells. Her designs are as much ritual as accessory — gender-neutral, spiritual, and unapologetically African. She is not alone. Melissa Simon-Hartman’s Cowrie Rebellion Belt electrified Black Is King’s “Mood 4 Eva.” Gambian brand Aajiya adorned Gabrielle Union in its Pétaw collection. Lupita Nyong’o and Atlanta artist Fahamu Pecou have each embraced cowries: Pecou’s New World Egungun series sells internationally, blending Yoruba tradition with sharp commentary on Black identity.

Today, cowries no longer trade horses but they trade meaning, memory, and modern profit. In African craft markets, bracelets sell for $5, wall hangings for $30, and mirrors for hundreds. On Etsy, Dion’s headpieces fetch $100–$500, with shells costing just $2–$10 per hundred. Designers yield margins that colonial traders could only dream of. The global handmade jewelry market is projected to reach $1.5 billion by 2027, with cowries riding the wave of “Afro-bohemian” décor and fashion trending across Pinterest and Instagram. Ethical sourcing is becoming vital: Dion’s shells, bought in local markets, cost slightly more but protect artisans and culture. Sustainability sells, and in this, cowries are again ahead of their time.

Cowrie shells are no longer currency, but they remain capital. Once used to buy bodies in the slave trade, they now crown them in pride. From spiritual amulet to Beyoncé’s crown, from colonial stigma to global runway, the cowrie shell embodies African resilience. Its journey offers a blueprint for the future: honor heritage, sustain craft, and let culture lead commerce. Africa’s ancient currency has become its newest crown.