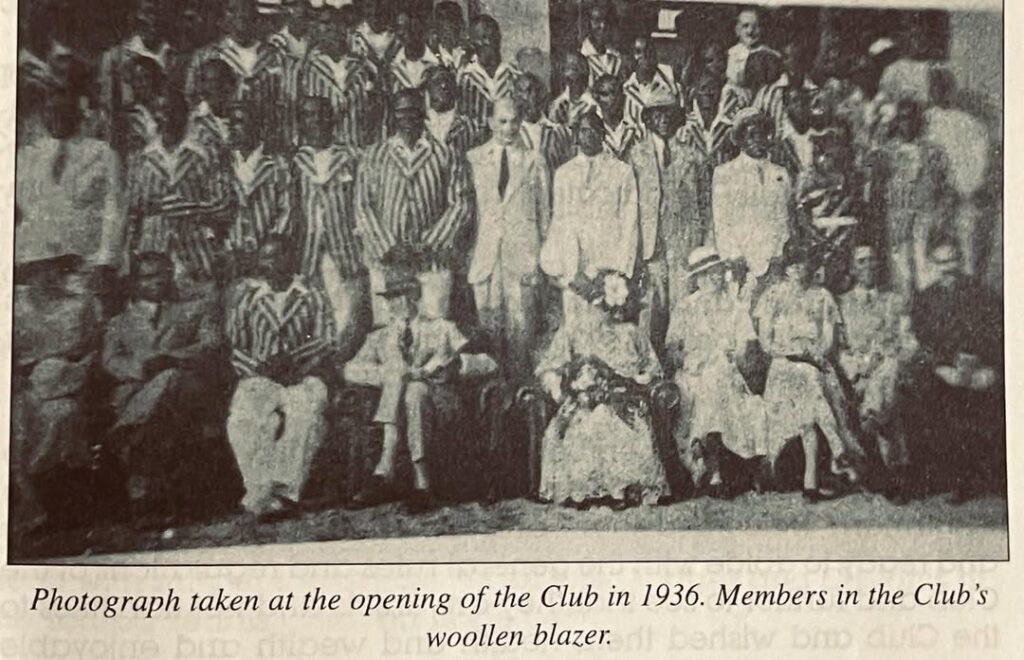

The first tennis clubs in Africa were built like fortresses. Behind their gates in Lagos, Johannesburg, Nairobi, and Casablanca, colonists played in pressed whites while Africans raked clay, carried balls, or stood outside the fence. The game was there but not for them.

That shadow framed a remark by South African designer Wanda Lephoto at the Met Museum’s Costume Institute program Continental Swagger: African Fashion Design in the 21st Century, moderated by scholar Monica L. Miller. “Black people were playing tennis in its early years, even as the sport was depicted as exclusively white,” Lephoto said. His reminder cut through a myth that still shapes the sport’s image today.

Nearly a century after the Yoruba Tennis Club was founded in Lagos in 1926 — created by Nigerians denied entry to European clubs — the U.S. Open is a different stage. As the 2025 main draw closes (August 24 – September 7), Africans and their descendants are no longer outside the gates. They are on the court, in the fashion, and central to the spectacle.

For much of the 20th century, structural barriers kept Black African players out of tennis’s top tiers. In apartheid South Africa, non-white players were barred from the same facilities and tournaments until the 1980s. Elsewhere, colonial clubs enforced their own exclusions.

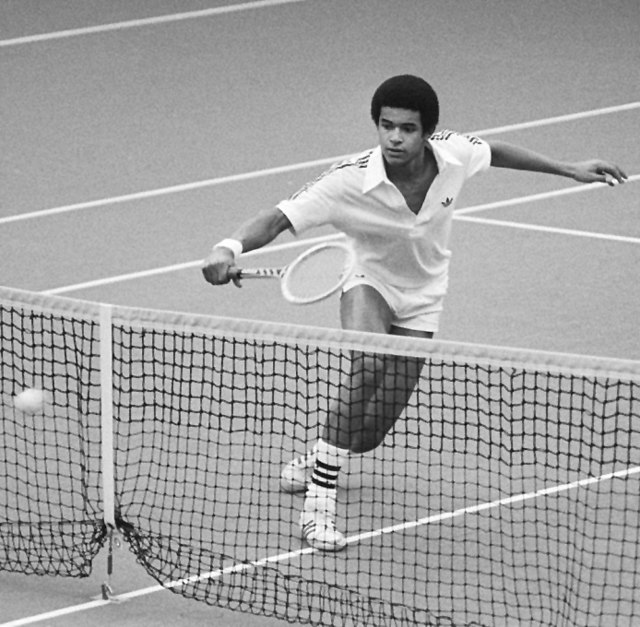

Change came slowly. By the 1970s, global tennis was professionalizing, and international pressure was mounting against segregated sport. Within this shifting climate, Ismail El Shafei of Egypt reached the fourth round of the U.S. Open in 1974, one of the first Africans to leave a mark in New York. Morocco’s Younes El Aynaoui followed with quarterfinals in 2002 and 2003, his endurance matches etching him into Open lore. And in 2022, Ons Jabeur of Tunisia became the first African and Arab woman to reach a U.S. Open final, her artistry turning Flushing Meadows into a site of continental pride.

Why North Africa first? Geography and colonial legacy. Moroccan, Egyptian, and Tunisian players had closer links to European circuits, access to coaching, and passports that made travel easier. Black South African players faced apartheid restrictions, while elsewhere in sub-Saharan Africa, weaker infrastructure and limited access delayed opportunities. Yet during this same period, white players from South Africa and Zimbabwe — Kevin Anderson (2017 finalist), Wayne Ferreira (1992 QF), Cliff Drysdale (1965 finalist), Cara Black (2008 doubles champion), and Lloyd Harris (2021 QF) advanced regularly, underscoring the stark divide in opportunity.

Against that backdrop, milestones like Mayar Sherif becoming the first Egyptian woman to win a Grand Slam match in 2020, or Yannick Noah, born in France, raised in Cameroon lifting the French Open in 1983, carried symbolic weight. They proved Africa wasn’t absent, only written out.

The U.S. Open today carries two intertwined strands of African presence: players from the continent itself, and those whose families trace their roots back through migration or diaspora.

Félix Auger-Aliassime, Canadian with a Togolese father, reached the semifinals in 2021. In 2025 he returned to the last four, before falling in four sets to world No. 1 Jannik Sinner — his best Grand Slam run in four years. Frances Tiafoe, son of Sierra Leonean immigrants, lit up Queens with a semifinal run in 2022. And this year, Victoria Mboko, 18 and Congolese-Canadian, stunned the tour in Montreal by beating both Coco Gauff and Naomi Osaka.

African American lineage adds another current. Althea Gibson cracked the color line in 1950, winning the U.S. Nationals in 1957 and 1958. Venus and Serena Williams transformed Arthur Ashe Stadium into a stage of Black dominance — eight singles titles between them, with Serena’s Virgil Abloh–designed tutu in 2018 becoming a cultural flashpoint.

Naomi Osaka, daughter of a Haitian father and Japanese mother, embodies another branch of diaspora multiplicity. She won the U.S. Open in 2018 and 2020, and in 2020 wore masks honoring Black victims of police violence. This year she returned to Queens, beating Coco Gauff in the fourth round and reaching her first Open quarterfinal since 2021, before falling to Amanda Anisimova.

Coco Gauff, 21 and the 2023 champion, left earlier than expected. Her fourth-round loss to Osaka was a hard one – she admitted afterward that it left her in tears but she was quick to frame it as fuel for what comes next. For Gauff, the U.S. Open remains a place to compete, but also to define culture in real time.

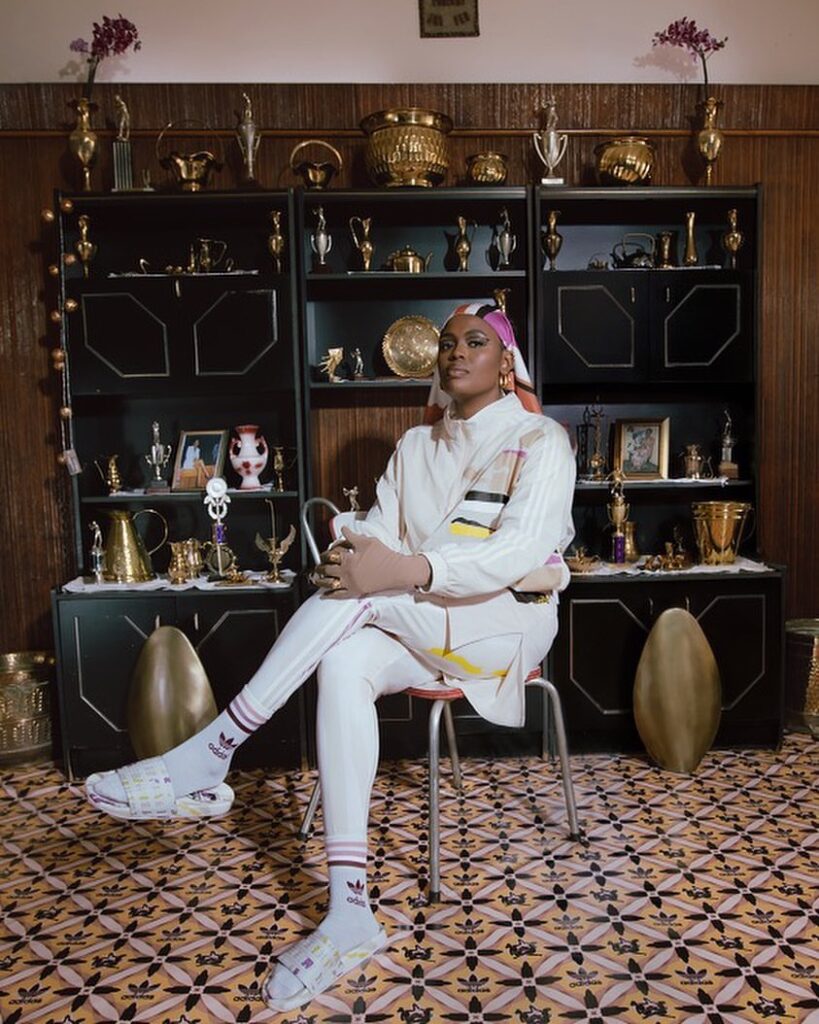

African influence isn’t only in the draw. In 2022, adidas unveiled a performance collection by Thebe Magugu, the South African designer celebrated for threading heritage into modern form. The line used inclusive UNITEFIT sizing and sustainable fabrics, debuting on athletes like Jessica Pegula and Félix Auger-Aliassime.

For a sport once defined by all-white dress codes, the sight was radical. It didn’t just signal African aesthetics entering tennis apparel; it confirmed that African design belongs in one of sport’s most visible arenas.

The story doesn’t begin with Venus and Serena. It starts with Althea Gibson, who won the U.S. Nationals twice in the 1950s. It extends through Yannick Noah, raised in Cameroon, whose 1983 French Open triumph remains iconic. It flows into Ons Jabeur’s U.S. Open final, Tiafoe’s semifinal, and Gauff’s trophy lift. And it carries through to Naomi Osaka’s return and Thebe Magugu’s designs under the lights of Arthur Ashe Stadium.

No Grand Slam has ever being hosted on African soil. That absence lingers. But the question of whether Africa belongs in tennis has already been answered. The challenge now is recognition – whether the sport will acknowledge Africa and its diaspora as central to its cultural history and future.