What do women hold onto when everything else feels uncertain?

Across Africa, one answer rises again and again: beauty rituals. In times of economic pressure, when inflation climbs and currencies wobble, many women continue to invest in small but powerful acts of adornment—braids, gele, fragrance oils, or a few yards of fabric.

Economists call it the lipstick effect: the tendency for people to spend on small, mood-boosting luxuries even when they cut back on bigger items. First observed in the U.S. and popularized by Estée Lauder chairman Leonard Lauder after 9/11, the so-called “lipstick index” tracked rising lipstick sales during economic downturns, including an 11% jump in 2008 as consumer confidence declined.

In Africa, the theory takes on a deeper, more layered meaning. Here, beauty is not just aesthetic. It is cultural, social, and often tied to identity and dignity. And with global inflation reshaping spending priorities everywhere, this insight feels especially urgent now.

Braiding as Resilience, Not Luxury

In Nigeria, Ghana, and Senegal, braiding isn’t optional—it’s ritual. From intricate cornrows to bold box braids, hair remains a cultural and emotional anchor.

During naira devaluations, fuel hikes, or inflation spikes, many women still prioritize getting their hair done. Even when other expenses are cut, a fresh set of braids remains non-negotiable.

“Even if I have just 10,000 naira, I will find a way to look neat,” says Rebecca, a Nigerian model in Lagos. “Hair is confidence.”

That confidence has tangible stakes. In a job market where first impressions can decide opportunity, a polished appearance becomes professional armor.

According to a 2022 Euromonitor report, hair care is the largest segment of Sub-Saharan Africa’s beauty market, driven by braiding salons and styling products. A 2020 McKinsey report similarly noted that, even amid economic pressure, beauty and personal care remained high-priority for urban African consumers.

As The Guardian Nigeria wrote in 2024:

“As the economy continues its downward slide… women do not tone down their hair expenses. Hair is the highlight of actual beauty — and looking good eventually amounts to good business.”

Nollywood: Escapism in Hard Times

The lipstick effect isn’t limited to beauty. It’s also about affordable escape. Just as Hollywood’s Golden Age thrived during the Great Depression, Nollywood emerged in the 1990s amid Nigeria’s economic instability and military rule.

With VHS technology lowering production costs, grassroots filmmakers began creating local stories on small budgets. Cheap to buy or rent, these films offered drama, romance, and cultural validation when daily life was hard.

Nollywood, like lipstick, became more than entertainment. It was affordable glamour and a mirror for ordinary people living through extraordinary times.

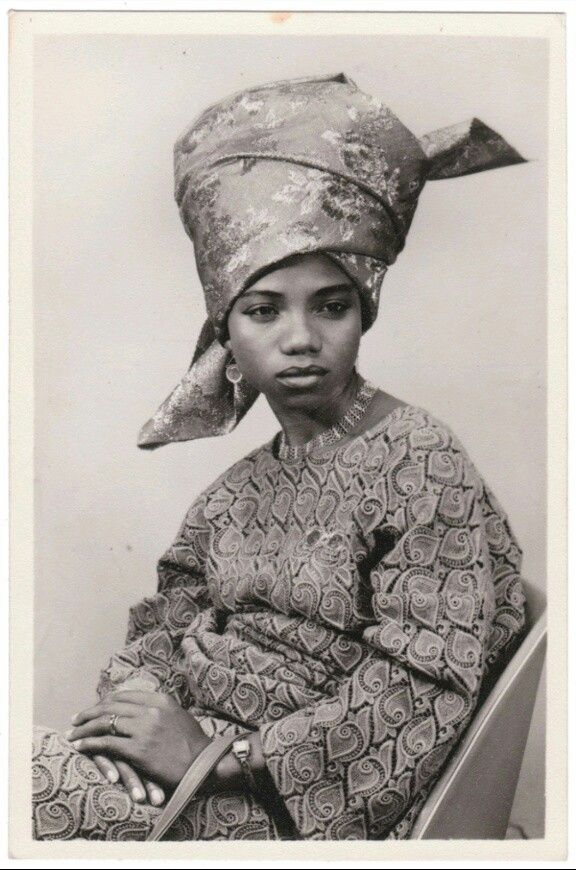

Gele and Fabric: Small Investments, Big Impact

Across Nigeria, Ghana, and East Africa, textiles carry economic and emotional weight. When money is tight, women may skip buying entire outfits but they will invest in a new gele or a couple of yards of Ankara or kitenge fabric for a special occasion.

One well-tied headwrap can transform a look and signal presence at weddings, funerals, or church services. These pieces aren’t just adornment. They are cultural statements of strength, celebration, and participation offering high visual impact for low cost.

Shea Butter, Black Soap, and Fragrance Oils: Beauty as Economy

In many parts of Africa, beauty products are not just self-care—they are micro-enterprises.

From Ghana to Sudan, affordable, locally made products like raw shea butter, black soap, and fragrance oils remain essentials. They are multi-use, culturally trusted, and accessible to women across income levels. For some, selling them sustains income; for others, using them sustains confidence and cultural connection.

More Than a Mood Boost

In the West, the lipstick effect is often seen as emotional spending. In African contexts, it’s layered with cultural heritage, public presentation, and economic survival. What Western economists often read as irrational spending looks like strategic investment in social and professional capital in African contexts.

Small luxuries—braids, fabric, oils, cosmetics—are not treated as indulgences. They are strategic choices. For many African women, to appear well-groomed and adorned in public isn’t a luxury. It’s a statement of power, pride, and self-worth. And often, it’s also practical: a good hairstyle can open professional doors. A strong look can inspire confidence. A well-wrapped gele can signal leadership, presence, and participation.

From street markets in Dakar to salons in Nairobi, the African version of the lipstick theory plays out daily. And it tells us something critical: In the face of inflation, scarcity, and economic precarity, people will still find ways to hold onto beauty—because beauty, in all its forms, is deeply tied to resilience and identity.

It may not always be a bullet-red lipstick. Sometimes it’s a shea butter glow. A perfectly parted braid. A gele knotted just right. But the message is the same: Because beauty, in this context, isn’t luxury. It’s life.