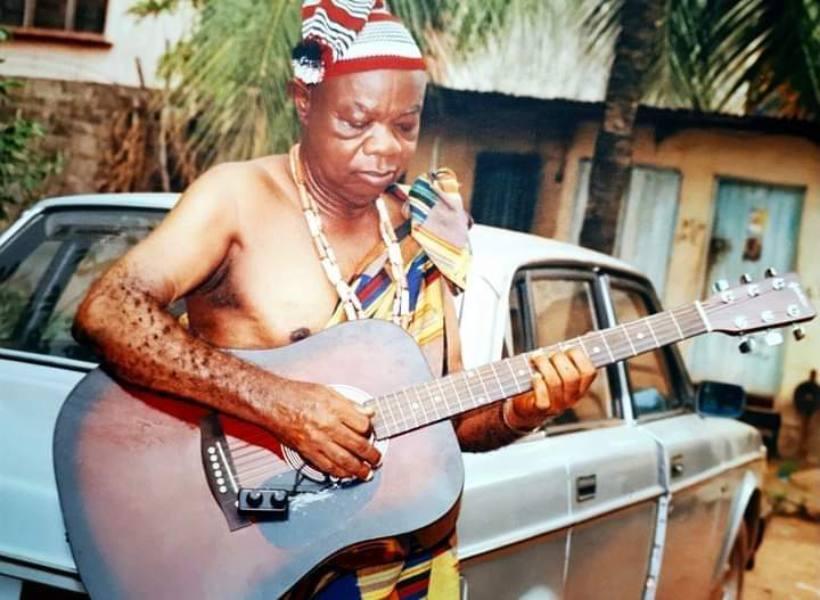

In July 2024, a Nigerian comedian named Brain Jotter posted a dance video to a song released in 1983. Within weeks, Gentleman Mike Ejeagha’s “Ka Esi Le Onye Isi Oche”—an Igbo highlife fable about a tortoise outwitting an elephant—had amassed tens of millions of views. By the time 2025’s year-end charts were tabulated, the track sat alongside releases from artists born decades after its recording.

Ejeagha died in June 2025 at ninety-five, but not before witnessing something extraordinary: a song he recorded in the early 1980s had found a second life through a platform that wouldn’t exist for another forty years. His story crystallizes what made 2025 different. This wasn’t simply another year of African music “going global”—that narrative has been running for a decade. This was the year the discovery mechanisms themselves transformed, and with them, the question of who gets heard.

Listen along

The numbers tell one story: Moliy’s “Shake It to the Max (FLY)” debuted at number ninety-one on the Billboard Hot 100 and reached number one on Shazam’s Global Top 200. Chella’s “My Darling,” released in March, became the fourth Nigerian song ever to top that same Shazam chart, joining CKay’s “Love Nwantiti” and Wizkid’s “Essence” in that rarefied company.

But the mechanism matters more than the metrics. Moliy, a Ghanaian-American artist previously known for her vocals on Amaarae’s “SAD GIRLZ LUV MONEY,” posted a snippet of “Shake It to the Max” from a birthday gathering in Ghana. No label strategy. No marketing budget. The video triggered a dance challenge that generated over two million user-created videos before the song was officially released. By the time the remix dropped in February—featuring Jamaican artists Shenseea and Skillibeng—the audience already existed.

This represents a fundamental inversion. The traditional pipeline—label signs artist, label releases song, label promotes song, audience discovers song—has been replaced by something more chaotic and more democratic. Chella went from his 2024 breakout “Yansh an Yansh” to topping global charts within months, his “My Darling” inspiring over two million TikTok posts before most industry gatekeepers knew his name.

Tyla’s 2025 was the kind of year that transforms an artist into an institution. The South African became the continent’s most-awarded artist, collecting twelve major prizes including the Billboard Women in Music Impact Award. She performed at Coachella, joined the Met Gala committee, and became the first African artist to sell out venues in both Thailand and the Philippines. Her “Push 2 Start” earned a Grammy nomination for Best African Music Performance.

But Tyla’s dominance exists within a broader pattern. Tems won the 2025 Grammy for Best African Music Performance for “Love Me Jeje”—her second Grammy, making her the Nigerian artist with the most wins. The song samples Seyi Sodimu’s 1997 original, another instance of catalog music finding new audiences. Ayra Starr’s “Gimme Dat” (with Wizkid) continued her evolution from breakout to establishment. Together, these women didn’t just chart—they shaped the year’s sonic vocabulary.

What makes this significant isn’t representation for its own sake. It’s that Tyla, Tems, and Ayra Starr each represent distinct sonic approaches—Tyla’s amapiano-inflected pop, Tems’ textured R&B, Ayra Starr’s bold Afropop—and each found global audiences without converging toward a single sound. The diversity survived the export.

Nigerian Afrobeats and South African Amapiano have dominated the conversation about African music’s global rise. 2025 complicated that binary. “Shake It to the Max” is fundamentally a Ghanaian production—Moliy from Accra, producer Silent Addy from the same scene—that found its crossover moment through a Ghana-Jamaica-dancehall fusion. The song’s success suggests that the next wave may not emerge from the established capitals at all.

Francophone Africa offered its own reminder. Gims, the Congolese-French artist born in Kinshasa, topped the French Singles Chart for seven weeks with “NINAO” and charted across Germany, Austria, Belgium, and Switzerland. His success operates through different infrastructure—European francophone markets rather than Anglophone Afrobeats pipelines—but the reach is undeniable. The continent’s musical export isn’t monolithic; it moves through multiple channels simultaneously.

Meanwhile, Amapiano’s trajectory showed signs of maturation rather than mere expansion. Tracks like “Biri Marung” (Mr Pilato, DJ Maphorisa, and collaborators) continued the genre’s global presence, but the breathless “Amapiano is taking over” coverage of previous years gave way to something more sustainable: integration. The sound now appears in unexpected contexts—remixes, productions, hybrid tracks—rather than announcing itself as novelty.

Rema’s “Baby (Is It a Crime)” exemplified a different kind of integration, sampling Sade Adu’s 1985 “Is It a Crime” to create something that honored both Afrobeats’ present and its diasporic antecedents. The sample choice wasn’t incidental—Sade, born in Ibadan, Nigeria, raised in England from age four, became the first Nigerian-born artist to win a Grammy in 1986. Rema’s interpolation connects today’s global Afrobeats moment to an earlier chapter of the same story.

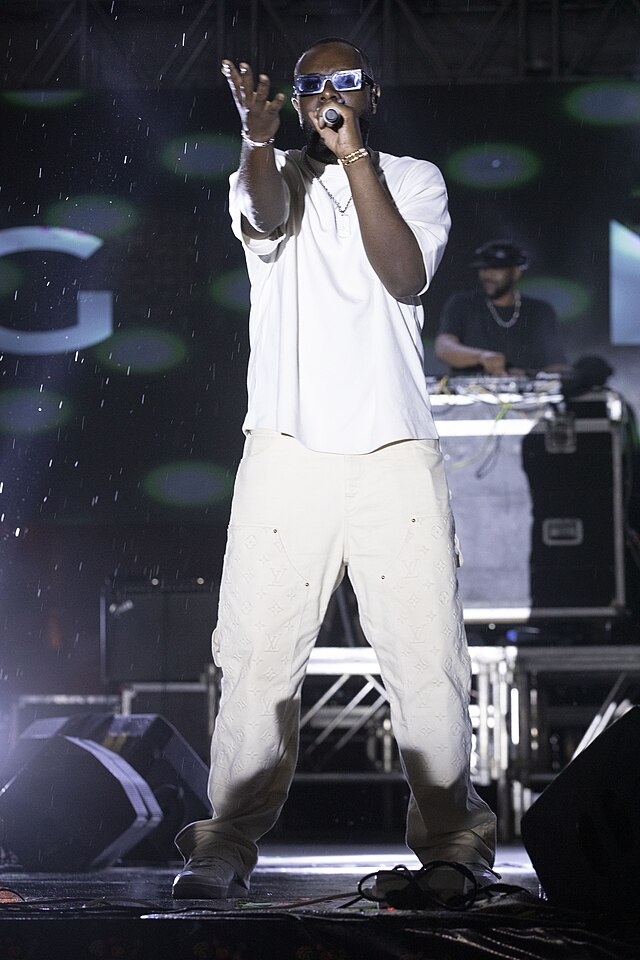

None of this disruption displaced the established order entirely. Davido’s “With You” featuring Omah Lay delivered exactly what fans expected—emotional depth, pristine production, two of Afrobeats’ most distinctive voices in conversation. Shallipopi’s “Laho” proved that street anthems still translate to global playlists when the energy is undeniable. Burna Boy maintained his position as the continent’s most visible ambassador through touring and releases that prioritized consistency over reinvention.

What changed is the relationship between establishment and emergence. A decade ago, breaking internationally required the machinery of major labels and Western media validation. Now, a viral moment can manufacture that machinery in weeks. The question facing established artists isn’t whether to participate in these new systems but how to maintain relevance within them.

The Grammy’s Best African Music Performance category, now in its second year, offers a useful lens. Tyla won in 2024 for “Water.” Tems won in 2025 for “Love Me Jeje.” Both victories went to women. Both artists built their followings through mechanisms that barely existed a decade ago—TikTok virality, streaming algorithms, global dance challenges. The category exists because African music’s commercial reality demanded recognition; the winners suggest where that reality is heading.

Gentleman Mike Ejeagha won’t chart again. But the systems that resurrected his forty-year-old song—algorithmic discovery, user-generated amplification, the collapse of distance between catalog and current—will continue reshaping who gets heard and how. The artists who understood this in 2025 aren’t just riding a moment. They’re building the infrastructure for what comes next.

Listen to the Year

Shake It to the Max (FLY) Remix — Moliy, Silent Addy, Skillibeng, Shenseea

My Darling — Chella

Biri Marung — Mr Pilato, Ego Slimflow, Tebogo G Mashego, Sje Konka, DJ Maphorisa, Scotts Maphuma, CowBoii

With You — Davido ft. Omah Lay

NINAO — Gims

Laho — Shallipopi

Ka Esi Le Onye Isi Oche — Gentleman Mike Ejeagha, His Trio

Baby (Is It a Crime) — Rema

Love Me Jeje — Tems

Funds — Davido, Odumodublvck, Chike

Chanel — Tyla

Push 2 Start — Tyla

Gimme Dat — Ayra Starr, Wizkid

Shake It to the Max (FLY) Remix — Moliy, Silent Addy, Skillibeng, Shenseea

Laho — Shallipopi