Zamrock musicians had no video of their heroes. They built a style from magazine photos and a Lusaka tailor.

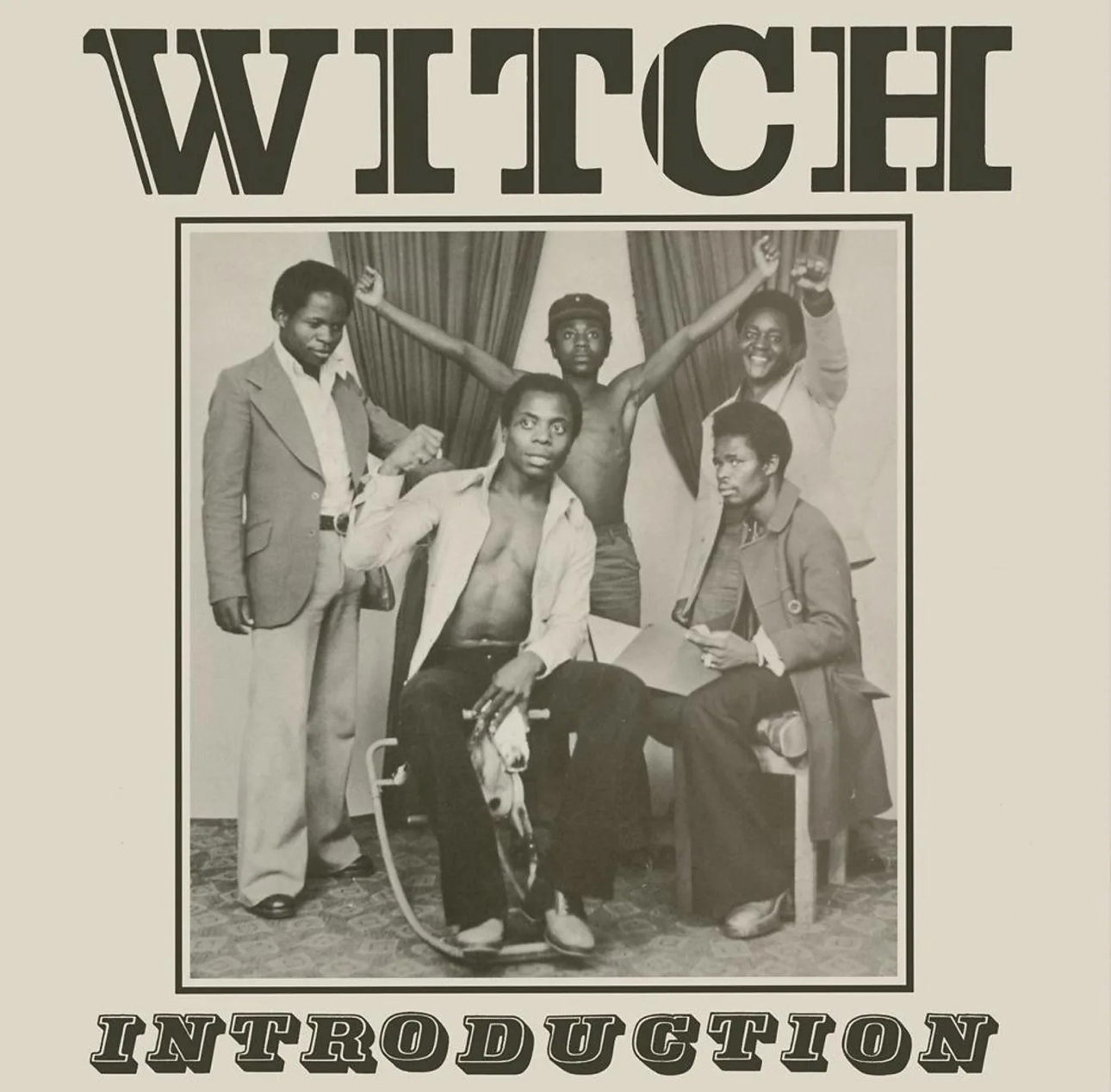

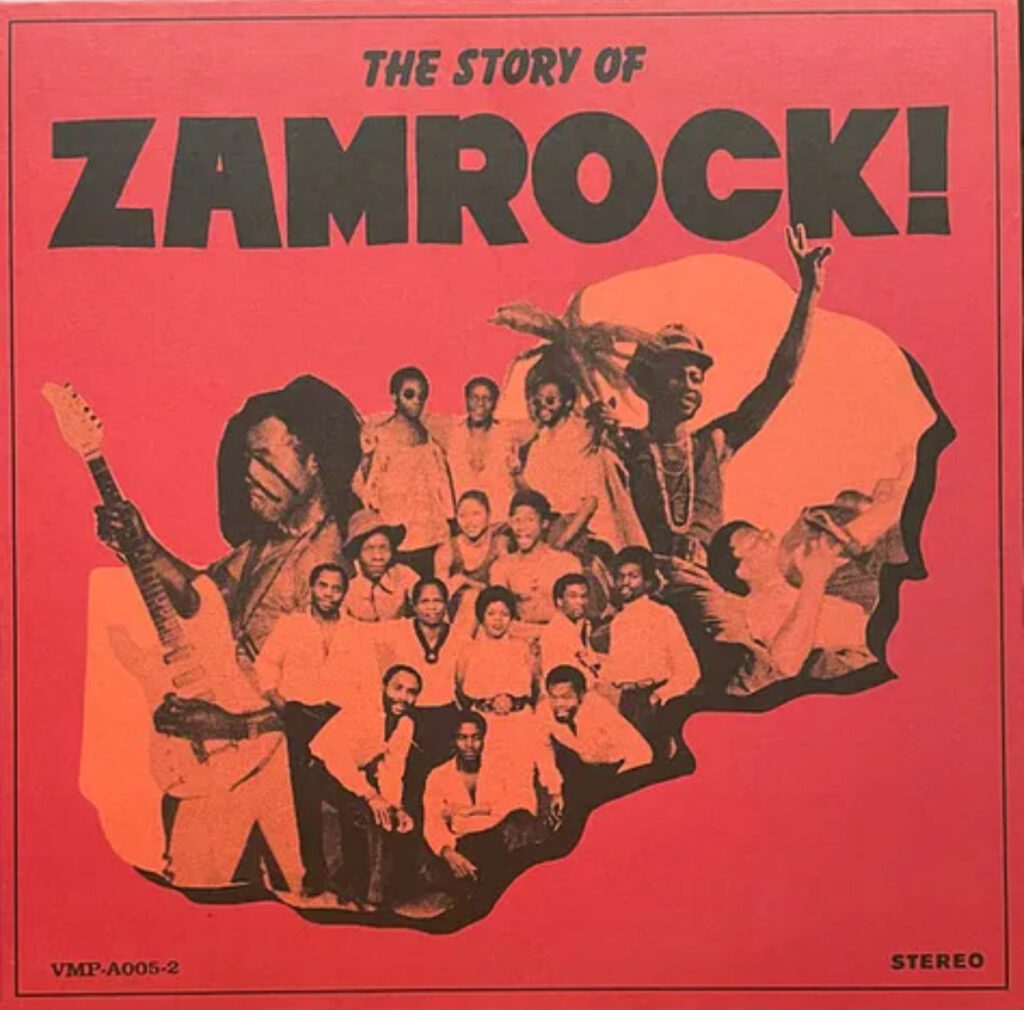

The cover of WITCH’s 1972 debut Introduction was photographed by John Chadwick and designed by Ro Barry. These are not famous names. They should be. What Chadwick and Barry produced—five men in a loose tableau, two seated, three standing, arms raised in casual triumph, a tailored jacket here, a bare chest there—was not documentation. It was invention. In a country eight years past colonial rule, with no template for what a Zambian rock band should look like, someone had to decide.

Zamrock musicians had no video footage of their Western influences. They heard rock on the radio and studied still photographs in imported copies of Melody Maker. Jagari Chanda, WITCH’s frontman, has described imagining what performers like Mick Jagger might be doing onstage based solely on magazine images. The result was not imitation. It was translation under constraint—a visual language built from inference, available materials, and the hands of specific craftsmen whose names have never entered the historical record the way their work deserves.

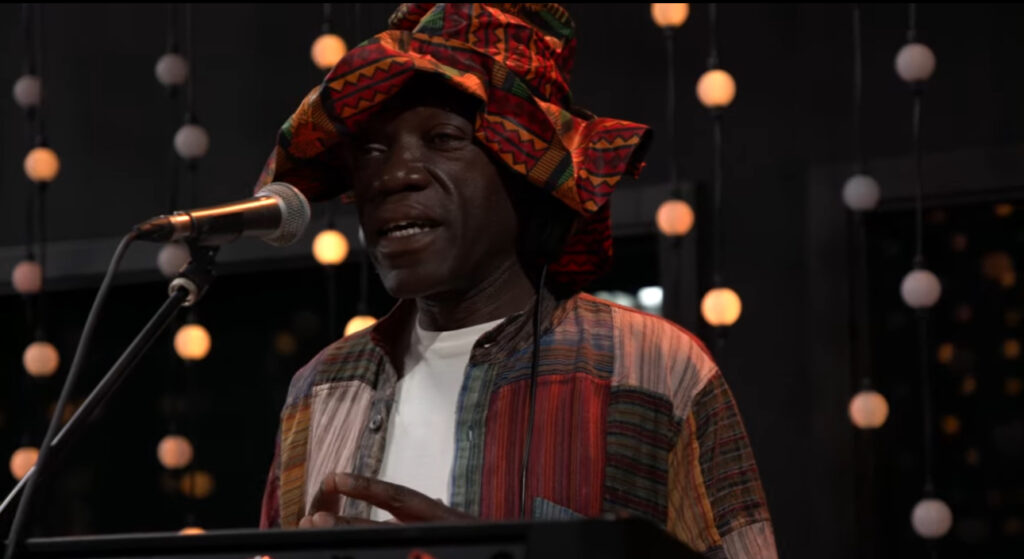

Emmanuel Kapembwa is one of those names. A Lusaka tailor, he made clothes for WITCH in the 1970s and continues crafting their outfits today. The most distinctive element of Zamrock presentation—the oversized floppy hat with a deep brim falling in sturdy pleats—came from his workshop. These hats were constructed from chitenge cloth, the printed fabric sold in Kamwala Market, fitted with an adjustable buckled strap. Kapembwa also tailored the bell-bottoms and the velvet suits in black and maroon. Western rock had a commercial wardrobe industry. Zamrock had a tailor who knew each musician’s measurements.

The platform boots told a different story. The custom platforms called unkada were ordered from Nairobi—handmade but with more professional construction than Lusaka could offer. On WITCH’s 1975 album Lazy Bones!!, they appear in yellow, orange, blue, and teal stripes. But a Times of Zambia article from the late 1970s documented young Zambians handmaking platforms from planks and animal skins. The style had jumped from stage to street. That is what fashion does when it works.

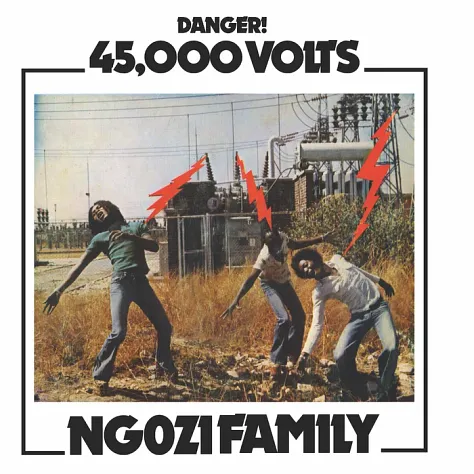

Norman Chisebuka Muntemba played bass for Salty Dog and designed album covers for Paul Ngozi, Keith Mlevhu, Ngozi Family, and others. He later founded Goman Advertising in Lusaka. A + S Graphics handled Amanaz’s Africa. Gilbert Advertising Ltd. did design and typesetting for WITCH’s Lazy Bones!! out of Ndola, the Copperbelt’s commercial hub. There was an infrastructure here—small, professional, resourceful. It has never been mapped.

Economics made it possible, then unmade it. At independence in 1964, Zambia’s copper industry generated a third of GDP and eighty percent of exports. Many Zamrock musicians were miners or miners’ sons, with money for velvet and Nairobi boots. The 1973 copper crash and oil crisis ended that. Import restrictions and inflation pushed the country toward salaula, the secondhand clothing markets. The scene’s arc—mid-70s peak to 80s collapse—followed the price of copper almost exactly.

Jagari has attributed the afro hairstyle to Jimi Hendrix, not Black Power. This matters. Tanzania banned afros in the 1970s as American cultural invasion. What African Americans reclaimed as a return to African roots, some African governments rejected as foreign imposition. Zamrock’s visual choices operated in a different symbolic field than their American counterparts—closer to Hendrix than Huey Newton, and a long way from Fela Kuti performing shirtless in Lagos, mocking Africans in Western suits.

Nearly all footage of Zamrock performance has been lost. The materials held at Zambia’s national broadcaster disappeared when the staff who maintained them died. What remains are the album covers. Now Again Records’ reissue program, researched by Eothen Alapatt and Zambian historian Leonard Koloko, recovered the photographs and credits. But album covers are not a fashion history. The names we have—Kapembwa, Muntemba, Chandia, Chadwick, Barry—are fragments. Who trained them? What did they look at? How did they understand what they were making? No one has asked, because Zamrock has been studied as music, not as design.

The floppy hat exists because someone solved problems: stage presence, sun protection, visual distinction, all at once. The handmade platforms exist because Nairobi was expensive and planks were not. Zamrock dressed the way it did not from imitation or rejection of the West, but from working with what was there. That is how style actually happens. It deserves to be studied that way.

Best of Culture 2025

Oury Sene