From the late 19th to mid-20th centuries, as European colonial powers carved up Africa, a sartorial uprising simmered beneath the surface. In the shadow of Union Jacks, tricolores, and Belgian crowns, African men—across Lagos’s humid docks, Accra’s dusty streets, Leopoldville’s riverfront markets—took the European suit, that rigid emblem of imperial control, and stitched it into a radical act of selfhood. This wasn’t just dressing well; it was dressing against. With every tailored seam and defiant accessory, they turned a tool of subjugation into a banner of power, dignity, and wit. As the 2025 Met Gala unveils “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” this colonial dandyism stands as a blazing testament to Black style’s resilience—a bridge from pre-colonial majesty to a global legacy of flair.

The Suit: A Colonial Imposition, Rewoven

When European colonizers swept in—British in West and East Africa, French in the Sahel and Senegal, Belgians in the Congo—they hauled more than guns and Bibles. They brought the suit: starched shirts, woolen vests, and double-breasted jackets, all cut for foggy London or breezy Paris, not the equatorial sun. Clothing became a colonial leash. Missionaries swaddled converts in ill-fitting hand-me-downs, their cotton collars chafing against sweat-slicked necks. District officers dressed their African clerks in faded blazers, badges of servitude. Schools drilled boys in khaki shorts and ties, preaching that “civilization” hung on a hanger. The suit wasn’t optional—it was a uniform of assimilation, a visual shackle meant to bleach out “savagery” and mold subjects into pale imitations.

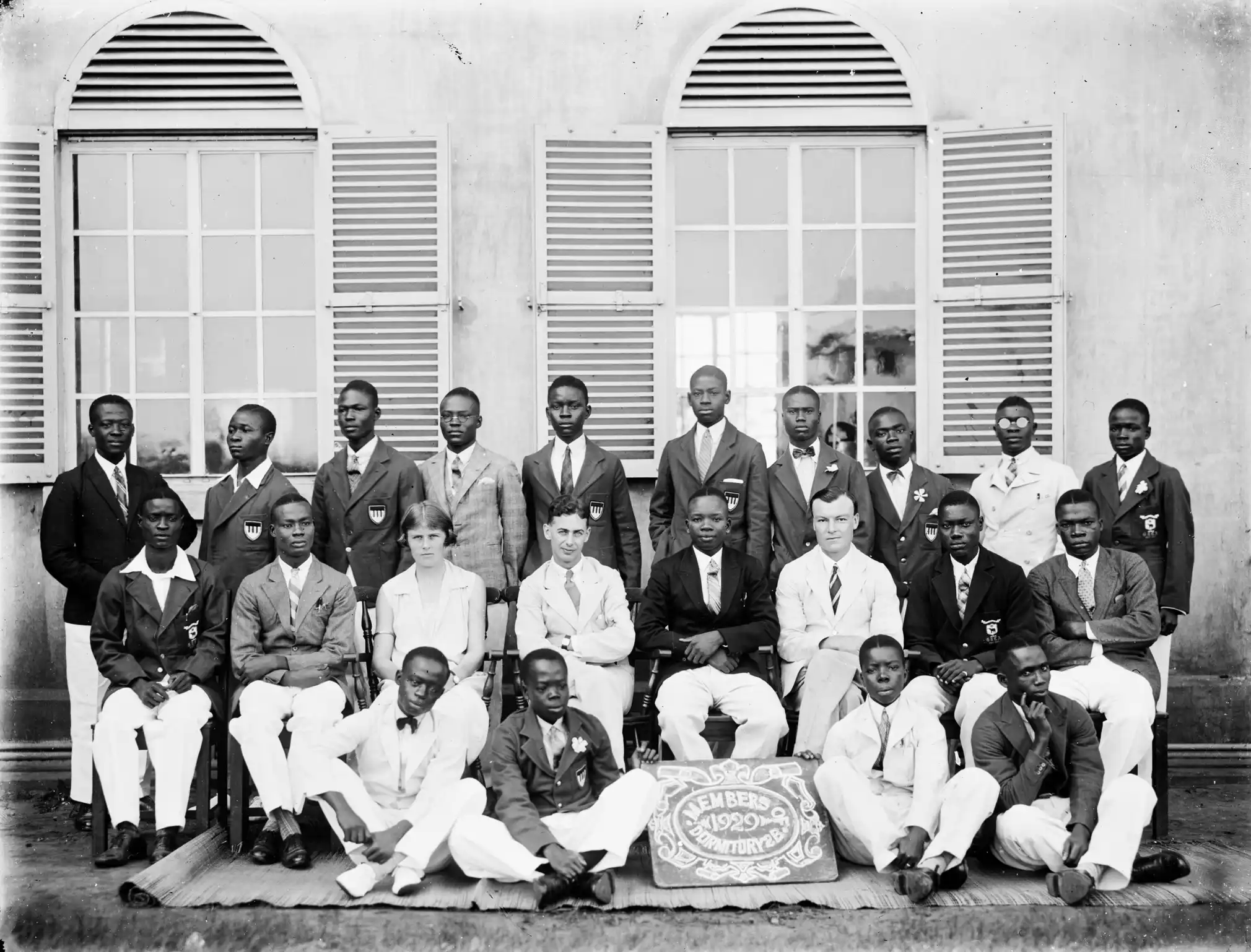

But African men didn’t bend. In Lagos, a Yoruba trader might stride from the harbor in a three-piece suit—charcoal gray, impeccably fitted—its lapels sharp as a blade. In Gold Coast ( Accra) a Ga teacher could do a pinstripe vest, then crown it with a headwrap. In Nairobi, a clerk might pair a secondhand British jacket with a beaded Maasai belt, its red and blue orbs clinking as he walked. These weren’t accidents of style—they were deliberate. Each fusion of European tailoring with African textiles screamed a truth: You can force the cloth, but not the soul.

Dandyism as Rebellion: Swagger in the Face of Chains

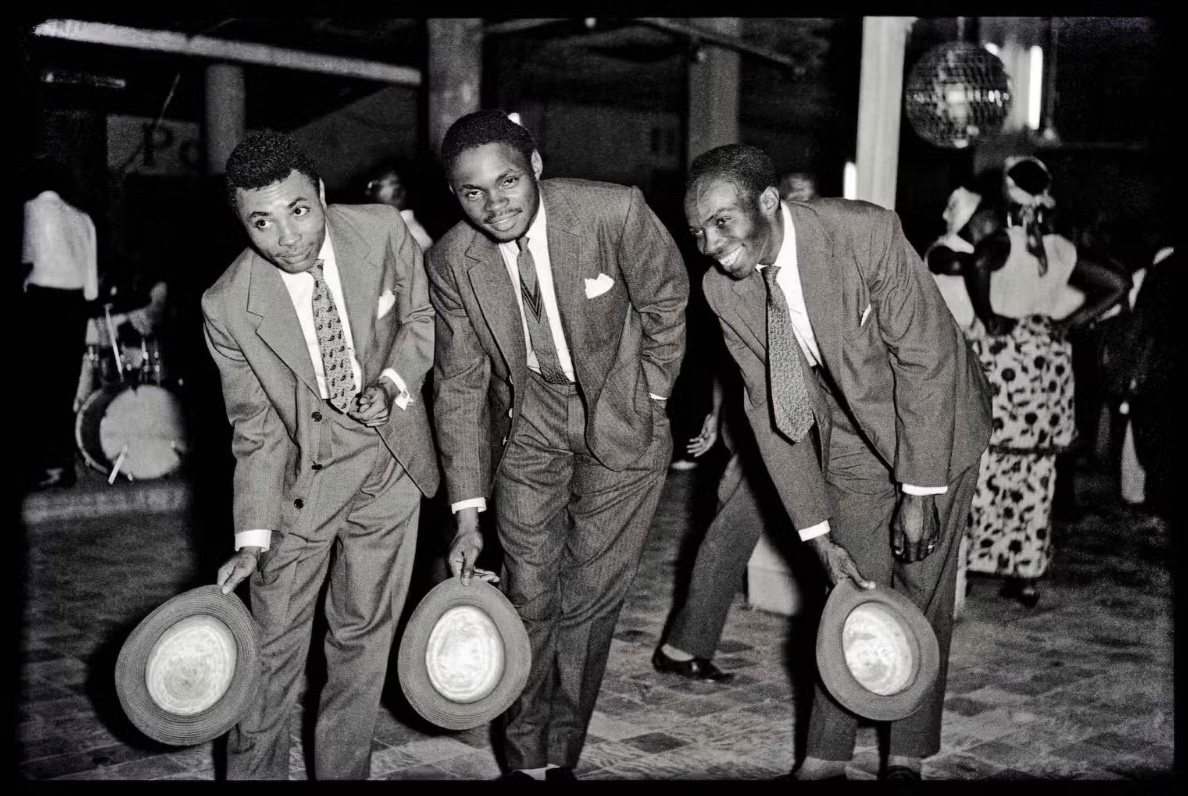

This wasn’t mere adaptation—it was war by wardrobe. The 18th-century dandies of France and England, with their ruffled cuffs and powdered wigs, had strutted as provocateurs against rigid norms. African men took that flame and lit a bonfire. Scholars call it a resistance movement, and they’re right—every buttoned vest was a brick in a wall against erasure. Picture it: a Senegalese dock worker in Dakar, his French-issue trousers rolled at the ankle, a waxed-cotton boubou flung over one shoulder like a cape, its geometric patterns mocking the drab khaki of his overseer. Or a Congolese sapeur avant la lettre in Kinshasa, his patched suit jacket gleaming with a borrowed sheen, a palm-leaf hat tilted rakishly as he danced past Belgian bureaucrats. These men didn’t just wear clothes—they wielded them, turning colonial scraps into arsenals of pride.

By the 1960s, this dandyism had ignited a subculture. In Ghana, the “Concert Party” performers rocked zoot suits with wide-brimmed hats, their stage swagger echoing from Accra to London. In South Africa, Sophiatown’s tsotsis paired pencil-thin trousers with bright suspenders, dodging apartheid’s gray grip. Word spread—photographs of these peacocks hit European papers, and African dandyism began its climb to global fame. The suit, once a shackle, became a spotlight. A fitted cuff sneered at missionary modesty. A kente tie spat at monochrome rule. These men walked through colonial cities—Lagos, Nairobi, Dakar—like living manifestos: We define power. We dictate style.

The Craft: Blending Roots with Ruin

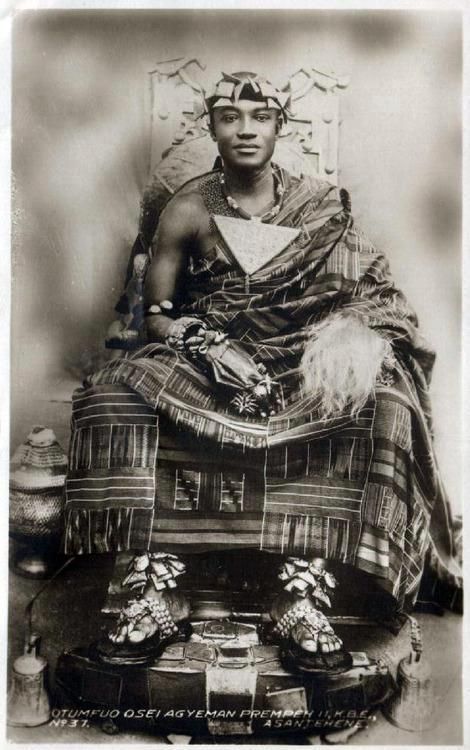

This dandyism wasn’t born in a vacuum—it grew from pre-colonial soil. The Ashanti kings’ kente, with its gold for wealth and blue for peace, didn’t vanish; it shrank into sashes, pocket squares, ties, draping over British wool like a conqueror’s flag. The Mali Empire’s indigo cotton, once flowing in desert robes, tightened into vests, its deep dye bleeding into French seams. Maasai shuka reds—symbols of warrior unity—snuck into linings or flared as capes over pinstripes. Fulani herders’ loose weaves met Belgian broadcloth, their breathability defying the sweat of tropical offices. Even the tools evolved: pre-colonial looms met Singer sewing machines, and tailors—often self-taught—stitched hybrid masterpieces in backrooms and market stalls.

Take a Lagos tailor in 1920: hunched over a treadle machine, he might cut a European jacket but line it with Adire cloth, its hand-dyed swirls a secret code of Yoruba pride. In Freetown, a Krio dandy could commission a suit from a Sierra Leonean seamstress, her scissors tracing Victorian patterns but her hands weaving in Mende motifs. This wasn’t mimicry—it was alchemy. Practicality (breathable layers for heat) met provocation (vibrant hues in a gray world), all grounded in the pre-colonial genius of form and function.

The Men: Faces of the Fight

Who were these dandies? Not just elites. The middle class—clerks scribbling in colonial ledgers, traders haggling in ports—led the charge, their modest wages funneled into bespoke cuts. But laborers joined too: a Johannesburg miner might save for a single-breasted jacket, wearing it Sundays with a Zulu beaded choker. Students rebelled in school uniforms, sneaking kanga cloth belts under blazers. Even rural men, far from urban tailors, adapted: a Luo fisherman in Kenya might knot a secondhand tie over a kanzu tunic, its white cotton glowing against Lake Victoria’s shore. They weren’t rich, but they were resourceful—pooling coins, bartering skills, turning cast-offs into couture.

Their stage was everywhere: a clerk tipping his hat in a Nairobi office, a trader twirling a cane in Dakar’s Marché Sandaga, a teacher lecturing in Accra with a kente stole flung over his shoulder. They drew stares—some mocking, some awed—but every glance fueled their fire. This was dandyism with teeth: elegance as survival, style as a shout.

Colonial dandyism didn’t just endure—it evolved. It laid the tracks for the 1960s sapeurs of Brazzaville, the Swenkas of apartheid South Africa, the global Black style icons of today. It’s the DNA of modern Afro-dandyism—where Oswald Boateng suit meets a Ghanaian wax print, where luxury and protest tangle. For “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style,” this is the pulse: African men, pinned under colonial weight, tailoring a future where Black elegance isn’t borrowed—it’s owned. From kente to pinstripes, from ochre to broadcloth, they stitched a lineage that struts into 2025, how is the future of dandyism looking?