Yagazie Emezi has never fit into one frame. A decade ago, she emerged as one of Nigeria’s most vital photojournalists. Today, her work moves between lens and loom, documenting African realities while threading ancestral narratives into textile art. Political yet intimate, her practice resists binaries of past and present, seen and unseen, reportage and ritual.

Raised in Aba, Nigeria, Emezi grew up surrounded not by cameras but by books and stories. “I was always creating—drawing, writing but photography came much later,” she says. A gifted camera in her early twenties became her passport into a new language. Traveling, she began to document not just places but the quiet choreography of people’s lives. “That’s when it clicked. This was my language.”

Her path into photography was less a career plan than a survival instinct. Relocating to Lagos, the city’s intensity demanded to be captured. Coming from a smaller town, she used her phone to photograph everything. With no formal training, she built a portfolio image by image, risk by risk. Editors took notice. Assignments followed. Soon, her images were reframing conversations on conflict, gender, and resilience.

Projects like Re-learning Bodies (2019), which centered survivors of trauma reclaiming their bodies, and her #EndSARS coverage, now synonymous with Nigeria’s fight against police brutality, cemented her voice. Yet Emezi is quick to push against being flattened into a single narrative.

“I’ve listened to and photographed stories that carry immense pain and loss… but I have also photographed so many tales of joy and triumph,” she says. “Successful c-sections in refugee camps, women actively creating change, simple everyday happiness—I always leave with something.”

Even at the height of her career, a deeper pull began to emerge. Constant travel left little space for self-directed creation. “I realized true fulfillment wasn’t in the next expedition but in creating intentionally,” she says. Without a permanent studio, she improvised—turning hotel rooms into makeshift workspaces, borrowing galleries, and eventually turning down high-profile assignments to meet exhibition deadlines. “I had to treat my art practice with the same urgency as my assignments,” she recalls. “That discipline was everything.”

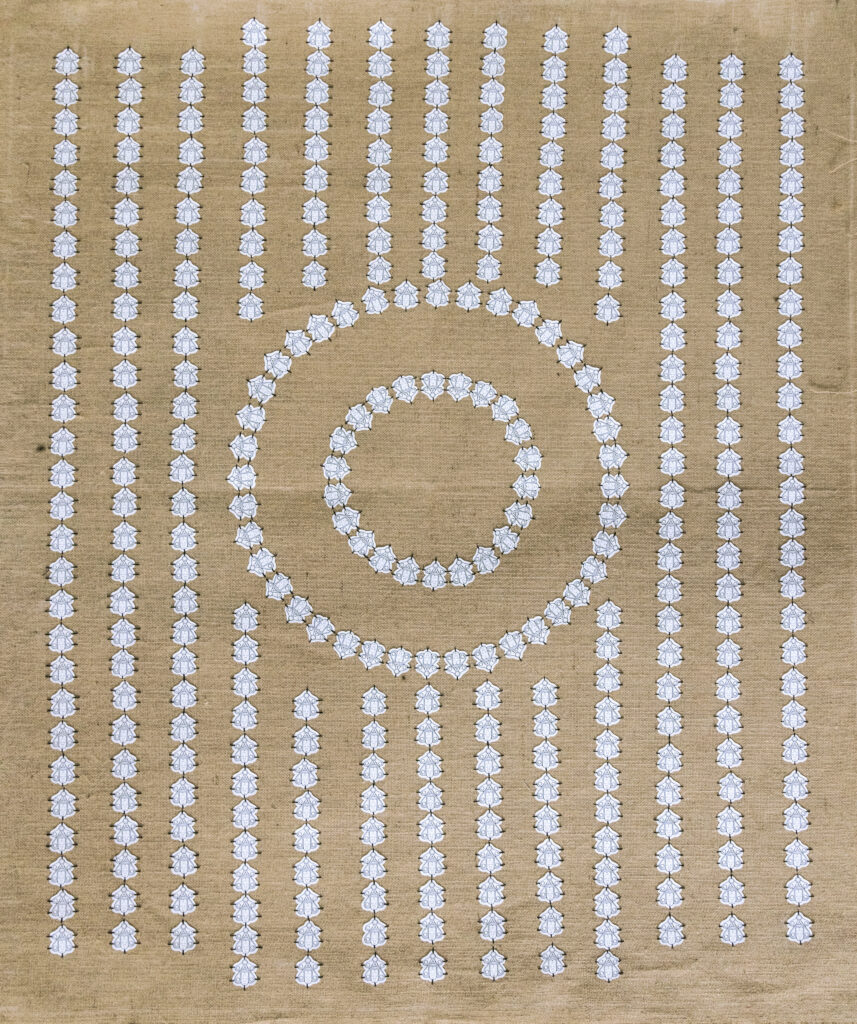

That discipline birthed a new chapter. In her textile installations layered with uli motifs and Igbo cosmology, Emezi’s work moved from documentation to invocation. Here, her spiritual practice became central.

“I work from the spiritual into the material, and with this comes ritual as a vital part of my process where I receive direction, clarity, and imagery,” she explains. “I work in collaboration with my Chi, my personal spirit. My body is an archive of ancestral knowledge that can be remembered and reinterpreted. With my Chi, there is legitimacy in what comes to me, and that carries the weight of my lineage.”

Her series I Keep My Visions to Myself marks this shift. The title came after a pivotal encounter two years ago. “I met a psychic for the first time, very skeptically. I wasn’t expecting anything,” she says. “But this stranger asked about the spirits I used to see as a child—something I had never told anyone. I had chalked those moments up to imagination. Hearing them spoken back to me unprompted shifted everything.”

For Emezi, the experience unlocked what she once dismissed. The title became both an admission and a release: the visions were no longer kept—they were translated into form.

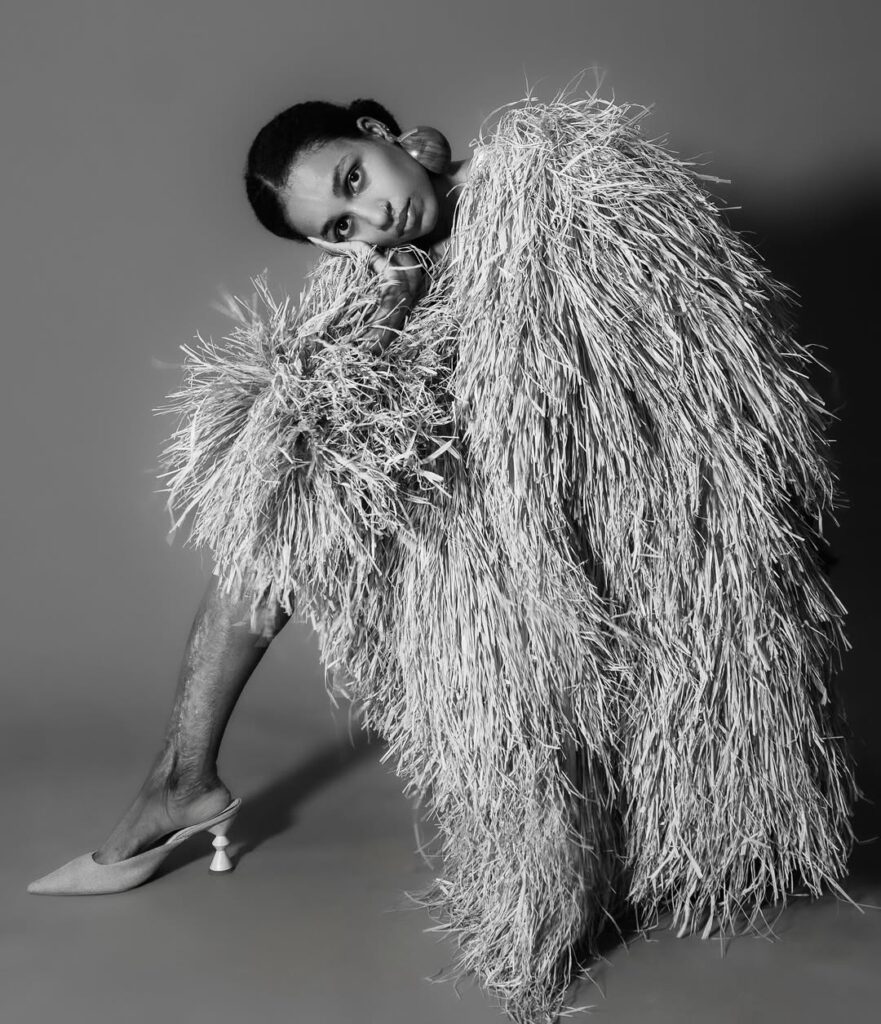

At Hannah Traore Gallery, her piece Fall to Ala carries that conversation between vision and material further. The work references a well-known Nigerian folktale about the Tortoise, a trickster who convinces the birds of the Animal Kingdom to each lend him a feather so he can attend a feast in the sky. He insists they call him “All of you,” so when the host announces the meal is for “all of you,” Tortoise alone eats. Angry, the birds reclaim their feathers, leaving him to fall back to Earth, his shell cracking into the patterns we see today.

“In my piece, Ala, our Igbo Earth deity, is represented in my embroidered motif. The falling self-portraits represent both a personal and collective descent—a fall from grace and a return to Earth. And despite our moral failures, Ala remains present. She receives us. She takes us back. The cycle continues.”

Emezi calls herself “still a photojournalist and a forever practicing photographer,” but emphasizes that her evolution is expansion, not departure. Her work is less a career than a continuum: between image and spirit, archive and vision, memory and material.

It’s a quiet power—one that moves African storytelling beyond the frame and into something living, unseen, and deeply felt.