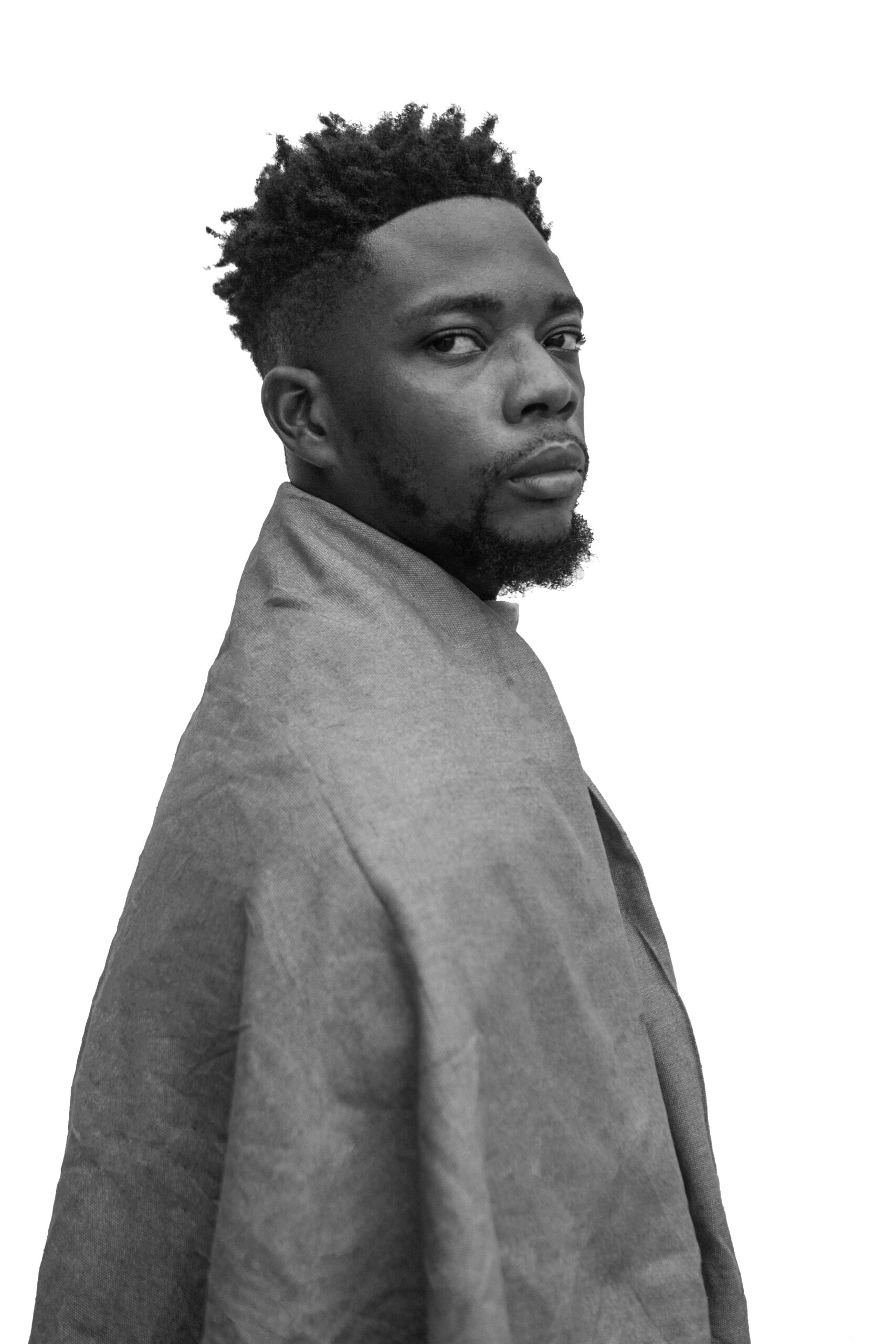

The paint beneath Oscar Korbla Mawuli Awuku’s fingernails is permanent. On a humid October morning in his Osu studio—a sun-drenched warehouse of light and pigment—the 28-year-old artist leans against a paint-spattered table, its surface crowded with brushes and glass jars.

We’ve come to discuss Anansinisim, the visual language he invented. But Awuku insists on beginning at the source.

“My first encounter with the masquerades was filled with fear,” he recalls. “But that fear came from not knowing. As I grew, I began to understand the cultural purpose behind them: keepers of memory, protectors of community, carriers of ancestral wisdom. What once terrified me slowly became a source of fascination. I realized the fear was never about the masquerade itself, but about the distance created between us and our own traditions. So I chose to turn that fear into curiosity, and curiosity into inspiration.”

At Mawuli School, where he studied visual art, that distance collapsed. The patterns that once haunted him became the foundation of Anansinisim—a system rooted in Adinkra symbols and the myth of Ananse the spider.

“Anansinisim is a visual language inspired by the spider’s web: its patterns, its complexity, its symbolism,” Awuku explains. “It also draws from traditional body painting practices across Ghana and the broader African continent. It’s a unique pattern painted on the body that weaves together the wisdom of the past with the identity of the present. I describe it as a living archive, an evolving form of expression that reconnects us with community knowledge, personal memory, and ancestral philosophy.”

Skin, he argues, is humanity’s original medium. “The human body is the first canvas we are given,” Awuku says. “Long before paper and galleries, culture was carried on skin—through scarification, body art, performance, and ritual. The body holds emotions, traumas, and histories that words cannot always express. By painting directly onto the body, I’m not just creating images. I’m engaging with identity, presence, and memory in their most intimate form.”

When he paints, silence reigns. “It’s a silent dialogue, built on trust,” he notes. “The body speaks through breath, stillness, posture, and energy. My role is to hold a shared space where identity is not being performed, but revealed through an artistic lens.”

His creative method is threefold: “Painting prepares both the body and the spirit, setting the tone for transformation. Photography then captures that transformation in visual form. Performance creates an immersive experience—one that engages both the performer and the audience in real time, later preserved through visual documentation. Each element is incomplete without the others. Together, they create an experience where the subject doesn’t just pose—they become the story.”

The spider deity Ananse, central to his practice, revealed a deeper lesson. “A close study of Ananse the spider teaches that creativity isn’t just about skill—it’s about wisdom, adaptability, and sharing knowledge. The spider’s web reminds us that everything is connected: one thread affects the whole structure. Creativity, to me, is a web of relationships between artist and subject, tradition and modernity, body and spirit.”

Two Adinkra symbols anchor his work. “Sankofa is very powerful to me,” Awuku says. “The idea of going back to retrieve what is lost has shaped my entire artistic path. Aya, a symbol I often paint on the body, represents resilience and endurance. These symbols remind me to stay rooted in culture while growing with courage and intention.”

Last month, Awuku unveiled Anansinisim: Body of Oracle—both book and solo exhibition—at the Accra Arts Centre, Centre for National Culture. Curated by Eric Nana Yaw Agyare, the opening drew Togbi James Ocloo V, Paramount Chief of Keta; Togbi Kludzehe IV, the Afetorfia of Ho-Bankoe; dignitaries from the National Commission on Culture; and his manager, Jade Enjoli Gold.

Yet the defining moment, he says, was quiet. “The most transformative realization was that the book launch and solo exhibition weren’t just about aesthetics—they were about healing. I watched people engage deeply with the works, especially the Ludu game reimagined with my patterns and fine art photographs, which functioned as an interactive sculptural piece. Some visitors simply stood in silence. Others questioned how someone my age could create work with such depth and spiritual resonance. In those moments, the art became a mirror, allowing people to see themselves, their histories, and their emotions differently. That experience changed me.”

All images courtesy of Oscar Korbla