When William Matlala picked up his mother’s camera in the early 1980s, he began what would become one of South Africa’s most quietly powerful photographic projects: a visually dense archive of factory floors, miners, families, and community life that refused the narrow images of Black existence under apartheid. Even after decades, his work continues to speak.

Matlala was born in 1957 to a family of eight children, during the early years of apartheid, which would last for 46 years. When asked what it was like, he says:

“It was as difficult as you imagine, every move you made was dictated as a black person and you had to carry your pass ID with you, if not you would go to jail.”

Apartheid’s pass laws, job reservation policies, and migrant labor system restricted nearly every aspect of Black workers’ lives. Against this backdrop, Matlala began his working life on production lines as a factory worker in the early 1980s—sites that would later become the subjects of his images: packing plants, workshops, and the social spaces that emerged around labour. While working as a machine operator, a shop steward, and a participant in the rising trade-union movement, he taught himself to see beyond. Encouraged by his co-workers, he began taking their portraits.

“They liked the idea of photographing them and urged me to. It was why I started my training, usually just anything I could see, maybe the machines or just them working,” he tells Guzangs.

He photographed his co-workers, street scenes, and community rituals, creating contact sheets and negatives that have become a lens through which life during the middle and late apartheid can be seen. His archive includes women bent over sewing machines in their homes, union delegates gathered in crowded halls, and families repairing roads or milking cows together.

Over decades, Matlala amassed more than 250,000 images. “It may sound like a speculation,” he explains, “but it is definitely true considering I’ve been with a camera since 1984.” A closer look at these images traces not only the struggles of Black workers but also the pride associated with a labouring life. One of his most prominent projects, Sewing at Home, captures the resilience of those who left factory jobs to build livelihoods through garment-making, turning necessity into craft.

Matlala’s photographs are documentary in the plain sense—black-and-white portraits, group shots, interiors of workshops, and close-up gestures of hands and faces. But collectively they form what critics call a counter-archive: a visual testimony created by people seldom afforded dignity by official record-keepers.

In this sense, his work sits in conversation with Ernest Cole’s House of Bondage (1967), which exposed the brutal machinery of apartheid, and Santu Mofokeng’s community-centered images from the 1980s, which explored spiritual and social life beyond oppression. Where Cole’s photographs revealed structural violence and Mofokeng’s sought the interior life of townships, Matlala’s archive offers a third register—labour itself as a site of dignity, pride, and resistance.

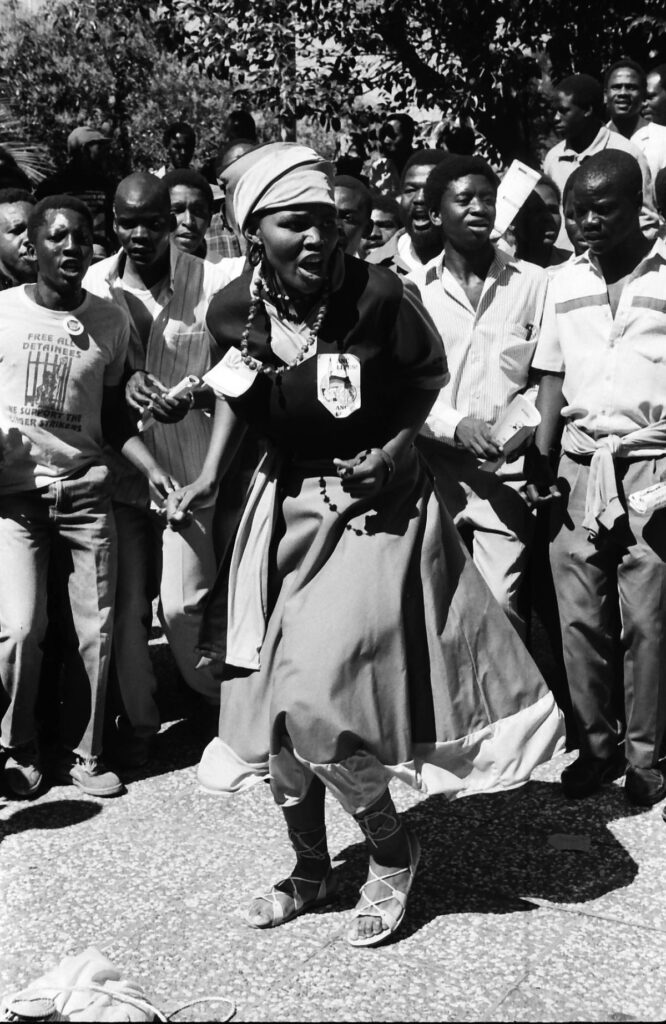

This is not to say Matlala’s camera avoided protest. Later work and selections from his archive show scenes of pickets, community assemblies, and mining towns. A union leader addressing a crowd, women in headscarves debating outside a factory gate, miners filing out of shafts—each image locates political resistance inside the broader texture of everyday life, connecting economic struggle, family life, and communal resilience.

Reviewers and curators note how Matlala constructed narrative sequences: one image answers another, negatives were reprinted for neighbors who had lost copies, and the archive functioned both as memory and as testimony.

For many years Matlala’s negatives lived in boxes and hard drives. Only in the last decade have curators and institutions begun to assemble and show his work more widely. Currently, an exhibition of his work appears alongside that of Zambian photographer Alick Phiri at Everyday Gallery Lusaka. Titled I’ll Be Your Mirror, it frames the practice as a refusal of invisibility, bringing together photographers who created counter-archives across Southern Africa.

“It is important to make exhibitions exploring the archive of William Matlala because it affords to engage with the last decade of apartheid and the period that followed from still underrepresented perspectives,” says Dr. Andrea Stulteins, co-curator of the exhibition alongside Sana Ginwalla. “The posers present themselves in front of the lens as they want to be seen, which is often in stark contrast to social documentary photographs of those days. While there are of course now impressive works by a younger generation of South African artists such as Lebohang Nkangye and Lindokuhle Sobekwa, it seems to me that ‘the world’ still needs to listen more to the generation who lived through the conditions of apartheid.”

Exhibiting Matlala alongside figures such as Cole and Mofokeng expands the canon of South African documentary photography, showing how different vantage points—structural critique, communal spirituality, and labour testimony—collectively resist the erasure of Black life under apartheid.

The show’s impact has already extended further. Andrea notes that it resulted in an invitation from Mandebele Photo Gallery in Soweto, where an adapted version will run from November 8, 2025, through February 7, 2026.

Over time, Matlala’s practice expanded from photography to documentary video. When asked why, he says:

“I saw the importance of those projects to be seen by the public in video format.”

His visual activism gained recognition for offering a textured counterpoint to the dominant images of violence that defined South Africa’s liberation struggle, revealing instead how dignity persisted through economic hardship.

Matlala’s photographs function as prompts: to read labour history not only through strikes and policy but through the ordinary gestures that made daily life possible, and to recognize photographers who documented their own communities as vital chroniclers.

“I wanted to expose parts of activities in life that are performed by the people themselves, so that a new generation could see and understand what life was then.”

On this Labor Day 2025, Guzangs commemorates his life, work, and vision. Matlala was more than a factory worker turned photographer — he was the one who took it upon himself to capture the moment so that future generations could understand what life was like under restricted freedom. His archive, vast and enduring, continues to shape the conversation around labour in modern times.

Today, as textile workers across Africa and gig workers globally still face invisibility, Matlala’s archive reminds us that documenting labour is itself an act of resistance. His images ask us to see and to honor the dignity of work.