When Bonhams launched the auction for Modern & Contemporary African Art in London, it added yet another chapter to the evolving story of how African and diaspora art is being valued and revalued on the global stage. Now scheduled for 8 October 2025, it will arrive with all the usual signals of a market-watching moment: a curated cross-section of established names, emergent voices, and a catalogue calibrated to attract both international collectors and Africa-focused buyers. But as is common in Bonhams auctions, not every lot will sell, and many will show a wide divergence from their pre-sale valuations.

One of the first lessons for anyone following the sale is that the price is never just the hammer figure. Bonhams, like other major houses, charges a buyer’s premium on top of the winning bid. In the UK, that means 28% on the first £40,000 and 27% on the amount above £40,000 (up to £800,000), before further lower tiers apply. The difference is not small. A painting hammered down at £40,000 will actually cost the buyer about £51,200 once fees are added.

The catalogue itself is built as a market test: paintings, drawings, sculpture and photography, spanning both established names and new entrants. It is designed to attract two audiences at once—global collectors who may be eyeing African art as a growing category, and Africa-focused buyers familiar with regional legacies. But catalogues also tell another story: not every lot will sell. Some will pass without a bid. Others will sell neatly within their estimate range.

Take Benedict Chukwukadibia Enwonwu (1917–1994), one of Nigeria’s most celebrated modernists. His catalogue lot Africa Dances (unframed) appears with a pre-sale estimate of £50,000–£80,000. Enwonwu’s oeuvre straddles painting and sculpture; his Anyanwu (in its monumental bronze version) is globally iconic, with smaller editions frequently making headlines when they reappear on the market. The fact that Bonhams devotes a mid five-figure slot to his painting signals confidence in his collector demand and a range wide enough that the work could either land conservatively or become a “surprise star” if bidding becomes aggressive.

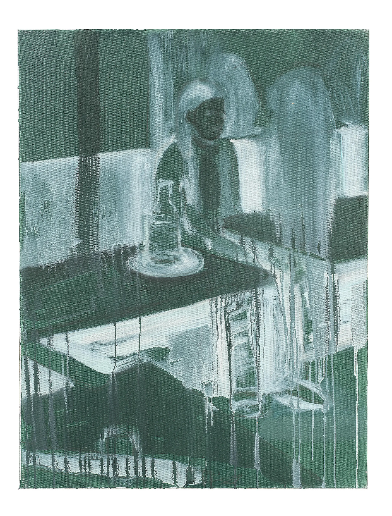

Then there is El Hadji Sy (Senegalese, born 1954) with Gathering seaweed (2009), a painting sized 92 × 75 cm. The auction page lists £7,000 as an estimate. Sy is known for his evocative seascapes, coastal narratives, and exploration of relationships between land, sea, and community. Because his market is younger and less saturated, works like Gathering seaweed may see more volatility: a low-end estimate that attracts entry bidders, or a surprise rush pushing it well above.

Next is Rom Isichei (Nigerian, born 1966), whose work Red Repose I is listed. The catalogue indicates a modest estimate starting from £3,000. Isichei is part of a generation of Nigerian painters working in contemporary figurative idioms; with fewer high-profile comparables than artists of Enwonwu’s generation, his lots are more exposed to variance—some likely to perform at the upper edge of expectations, others to languish near the lower bound.

Each of these artists represents different vectors of risk and potential in the catalogue. That mix is precisely what breeds price fluctuation.

For artists and collectors, these swings matter. High-flying sales can boost reputations and set new benchmarks, but they can also make the market appear more stable or buoyant than it really is. Conversely, unsold lots or steady within-estimate sales can reveal caution in a category often framed as on the rise.

For observers of African art in particular, this volatility cuts both ways. On one hand, it proves that international appetite exists and that collectors are willing to pay beyond expectations for works they value. On the other hand, it shows that not every artist or lot enjoys that surge; price growth is uneven, dependent on name recognition, provenance, and the psychology of a given day in the salesroom.