Before colonial rule, most communities wore practical, hand-made garments: woven cotton wrappers in West Africa; smocks and robes for traders and farmers; leather and beadwork in parts of the Sahel and southern Africa; wool and barkcloth where those were available; light cotton shawls like the shamma in the Horn; and long robes, haiks, and djellabas across North Africa. Clothing signaled work, age, status, and faith, updated season to season by tailors, weavers, dyers, and tanners using techniques passed down through families.

Colonialism didn’t invent “everyday wear,” but it standardized and policed it. Mission schools and offices pushed shirts, trousers, suits, and uniforms. Modesty rules reshaped silhouettes. Imported mills and secondhand markets undercut local makers, and new cash economies favored cheaper factory cloth over handwoven textiles. Islam and Christianity had already influenced dress in many regions, but colonial bureaucracy made Western styles a ticket to jobs and social mobility.In this piece, we examine the politics of clothing—how imported ideas of dress shaped what Africans wear today, for better and for worse. Mass-made garments made style accessible but pushed local industries to the margins. Yet modern African fashion is not simply a copy of the West; it’s a remix. Wax prints with colonial roots are cut by local tailors, streetwear meets indigo dye, and suits are worn with aso-oke caps. Each outfit now holds a quiet rebellion—a reminder that style on this continent has always been about adaptation, identity, and choice.

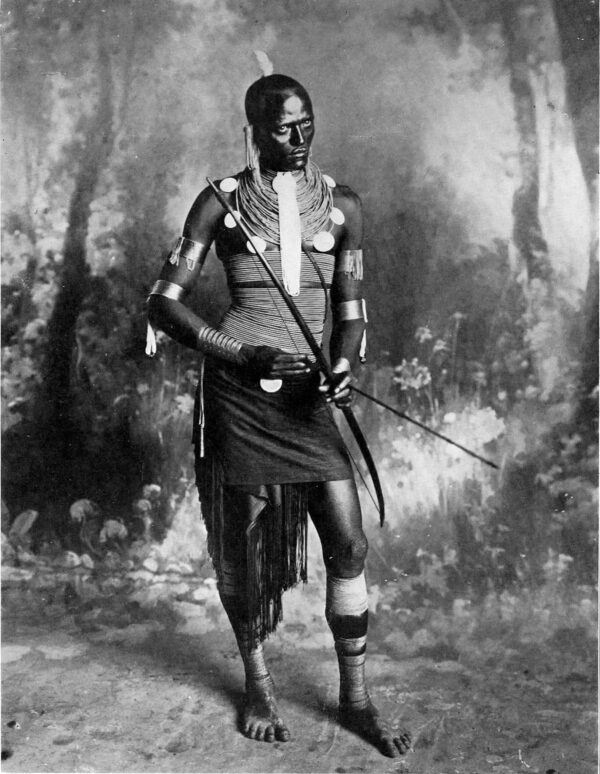

When European missionaries and administrators came to the continent, they didn’t just import religion and governance—they imported a moral framework that disapproved of bare African bodies adorned with ornament, painted, beaded, wrapped in cloth that danced with identity. Modesty, defined through the prism of Victorian and Edwardian sensibilities, was treated as evidence of civility. Bare skin was cast as heathen. Ornate local adornment was condemned as vanity.

Through mission schools and church pews, colonial regimes embedded dress as a disciplinary tool, a way to make African bodies visibly obedient to foreign moral codes. Fold by fold, the values shifted: exposure came to equal shame, covering equal virtue. By the mid-20th century, clothing had become a visual taxonomy of colonial order—Western attire was civilized, local attire primitive.

Yet as independence swept through the continent, these imported aesthetics didn’t simply vanish. They fused with local hierarchies to form something hybrid: a modesty that was neither wholly foreign nor fully indigenous. Even as nationalist movements called for cultural pride, the visual grammar of decency still mirrored the colonizer’s gaze. In many countries, the modern African citizen was still imagined in a pressed shirt or neatly pleated skirt—disciplined, clothed, respectable. The body, once colonized through land and labor, was now colonized through fabric.

That colonial logic survives most clearly in the classroom. In different countries, dress codes remain less about practicality and more about policing morality. In Ghana, students with afro hair have been suspended under the guise of “school discipline.” In Nigeria, dyed hair, dreadlocks, fitted clothing, and long painted nails are still considered unprofessional. Kenya and Uganda have banned what they call “revealing uniforms,” claiming that modesty preserves respect. None of these rules improve learning or productivity—they are about producing moral citizens, bodies trained to conform.

Uniforms, in this sense, act as moral architecture. They flatten individuality into sameness, teaching children early that respectability demands obedience. Even in secular schools, religious notions of purity quietly shape policy. The female body, in particular, is treated as a disruption that must be managed: her fabric should not attract attention; her body must not distract. Over time, this becomes internalized—a quiet inheritance of control that teaches women their morality begins and ends at the seam of their skirt.

The church and mosque are not excluded. Sermons echo a familiar refrain: “dress decently.” Women’s clothing, in particular, is cast as the frontline of moral decline. A covered body signifies righteousness; a bare one, rebellion. Churches prescribe ankle-length dresses; mosques emphasize loose, layered fabric. But behind these injunctions lies something deeper than piety—a politics of visibility.

In societies grappling with economic hardship and shifting gender norms, the moral panic around dress becomes a proxy for social control. Religious leaders channel public frustration into bodily governance, transforming the wardrobe into a moral battlefield. Yet these same sermons often ignore the fashion economy they indirectly fuel. Entire industries now thrive on modest fashion: long-sleeved Ankara gowns, rebranded hijab couture, and conservative “African wear” marketed as empowerment. In a paradox of capitalism and control, modesty has become both virtue and commodity.

Hue by Idera. © Guzangs

Hue by Idera. © Guzangs

If religion moralizes fashion, the state enforces it. In Uganda, women are arrested for miniskirts; in Nigeria, men with dreadlocks or painted nails are profiled as criminals. The colonial gaze survives in uniform—morality and policing stitched into the same fabric.

For women, this fixation manifests as a double standard that ties virtue to fabric and holds them responsible for male behavior and perception. Every hemline becomes an act of negotiation, every cleavage a political statement. Public space demands modesty not as expression but as self-defense. Through this choreography of concealment, women are made to internalize the logic of their own policing.

For queer and gender-nonconforming Africans, the stakes are even higher. Clothing that strays from the binary—a man in eyeliner, a woman in tailored suits—becomes evidence of deviance and is often met with violent hostility. “Cross-dressing” laws, inherited from colonial penal codes, give police license to arrest people for existing visibly. In this context, fashion isn’t aesthetic; it’s survival. Every outfit is a calculation between truth and safety, between the right to exist and the need to disappear.

To be stylish in such environments is to risk visibility; to be visible is to risk punishment. The state’s fixation on modesty reasserts an old order: that power has the right to regulate the body. The irony is sharp—the same governments that proclaim “African values” enforce foreign moral codes through law enforcement. Modesty becomes performance art for authority, a theater of control where decency and deviance blur, patrolled by men with guns and God on their side.

Designers are amplifying this defiance, not through spectacle but through subtle recalibration. Nigerian designer Adeju Thompson, founder of Lagos Space Programme and winner of the International Woolmark Prize, cuts through gender with surgical precision, creating garments that feel like both past and prophecy. Thompson reimagines Yoruba adire—once coded as feminine—into genderless couture, reshaping fabric into philosophy. Wearing LSP is not just aesthetic; it’s political theater, a refusal to obey the gendered laws of decency.

In Ghana, Sammy Oteng threads protest into pattern, using recycled fabrics to champion sustainability and self-determination. In South Africa, Seif Kalo weaves local motifs into silhouettes that dissolve colonial respectability. Together, these designers form a chorus of rebellion—proof that culture and freedom are not enemies but co-conspirators.

This new couture does not beg for acceptance; it asserts existence. It makes clear that modesty, once weaponized to police the body, can be redefined by the body itself. Through fabric and form, a new Africa is emerging—one where style is not silence, but speech.