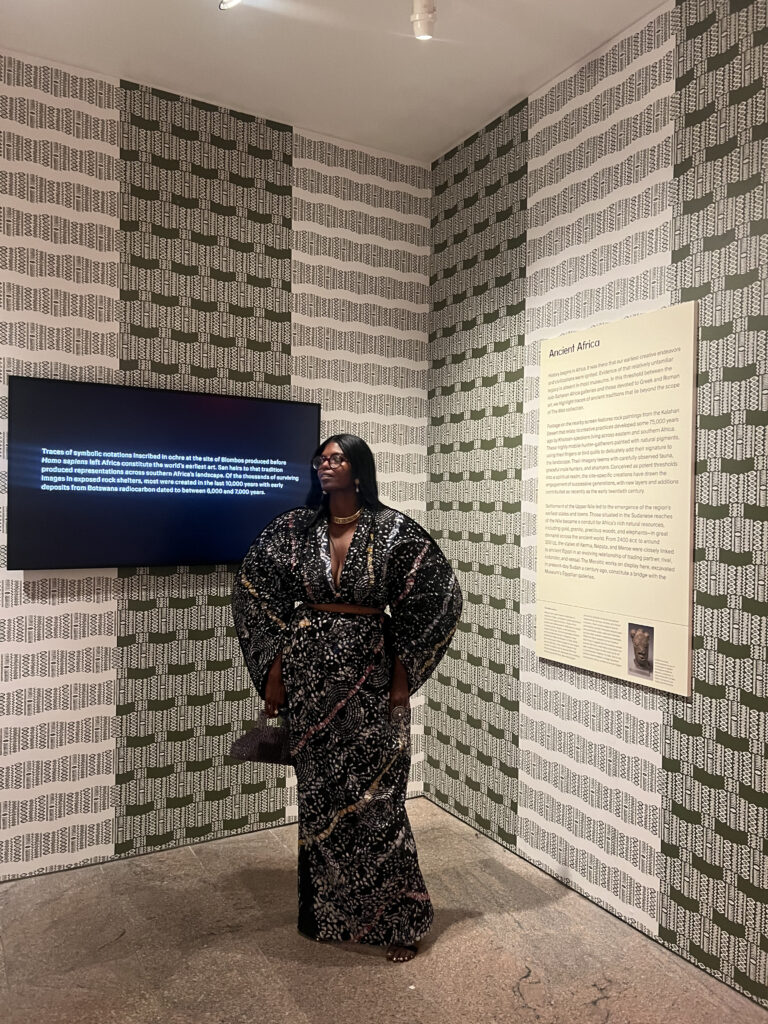

On May 31, 2025, New York’s Metropolitan Museum of Art (The Met) reopened its Arts of Africa galleries with a celebration that felt less like a formal unveiling and more like a long-awaited homecoming. The newly redesigned space, part of the Michael C. Rockefeller Wing, brought together artists, curators, collectors, and cultural leaders from across the city. But at its heart, the night was a tribute to African art—its beauty, its complexity, and its long-overdue institutional recognition. Guzangs attended a reception on May 28, held ahead of the official reopening, offering an early look at the transformed galleries.

In his opening remarks, Met President Max Hollein called the reopening a “monumental institutional pivot”—a fundamental shift in how African art is viewed, valued, and presented. His words resonated throughout the evening, culminating in a powerful performance by Beninese icon Angélique Kidjo, joined by fellow legends Youssou N’Dour and Baaba Maal. Draped in vibrant woven fabrics, Kidjo’s voice echoed through the galleries like an ancestral call, anchoring the celebration in rhythm, memory, and joy.

Closing the Doors to Open New Conversations

The Michael C. Rockefeller Wing had been closed since summer 2021 as part of a $70 million renovation project that reimagined how the Arts of Africa, the Ancient Americas, and Oceania are displayed. This wasn’t simply about a physical facelift—it was about a curatorial reset. The goal was to move from display to dialogue; from presenting objects as static artifacts to engaging them as living carriers of history, culture, and identity.

Centering Africa in the Canon

Inside the new galleries, over 500 works spanning from the 12th century to today are on display—nearly a third of which have never before been shown at The Met. From royal regalia to textiles, carved wood sculptures to photography, the works are no longer anonymized or decontextualized. Instead, they are credited, storied, and elevated.

Visitors are introduced to the legacy of Ọlọ́wẹ̀ of Ìsẹ̀—one of the most influential sculptors of the Yoruba world—and the monumental textile installations of Malian contemporary artist Abdoulaye Konaté. This is a shift away from the ethnographic lens through which African art has so often been viewed in Western institutions. Thanks to years of collaboration with African scholars, artists, and cultural thinkers, the galleries now echo with specificity, reverence, and respect.

From Land to Gallery: Tracing the Origins

A standout component of the new galleries is The Met’s digital storytelling initiative, developed in collaboration with the World Monuments Fund. The museum selected a dozen heritage sites across sub-Saharan Africa—from ancient ruins to modern cultural landmarks—and commissioned a series of short films to explore the living traditions tied to them.

Directed by Ethiopian-American filmmaker Sosena Solomon and co-produced with local cultural institutions in countries including Nigeria, Madagascar, Ghana, Benin, Uganda, and Botswana, the films delve into architecture, ritual, and community memory. These videos are not just background—they are embedded into the in-gallery experience and also accessible online, offering layered perspectives that expand far beyond the museum walls.

Architecture That Echoes Africa

Designed by Kulapat Yantrasast of WHY Architecture in partnership with Beyer Blinder Belle and The Met’s Design Department, the physical space breathes with intent. Light pours through slanted glass panels, inviting a conversation between architecture and sculpture. Structural gestures nod to regional vernaculars—the earthen geometry of Sahelian cities, the compound curves of Southern Africa. It doesn’t feel staged. It feels grounded. Alive.

What This Means for Africa’s Creative Future

The reopening of The Met’s Africa galleries is not an isolated cultural event—it’s part of a much wider tide. From Lagos to Luanda, Kigali to Abidjan, African artists, curators, and designers are leading a renaissance in how the continent’s stories are told, preserved, and monetized. Auction houses are paying attention. Art fairs like Art X Lagos and 1-54 are expanding. New institutions, such as Zeitz MOCAA in Cape Town and MACAAL in Marrakech, are shifting global reference points.

African fashion, too—long intertwined with art, memory, and resistance—is following suit. And in this broader creative ecosystem, The Met’s new galleries stand as proof: that African creativity does not need validation. It needs platforms. That Yoruba bronzes, Kongo cosmologies, and Malian textile traditions are not footnotes to Western art—they are foundational to the global canon.