Before silk lapels, velvet loafers, or custom-tailored suits graced the red carpet, African men were already masters of refined, intentional dress. In pre-colonial times, menswear across the continent was more than fabric — it was storytelling. Rich with symbolism, steeped in meaning, and crafted with care, clothing served as a powerful expression of identity, community, and spirituality.

As the 2025 Met Gala embraces the theme “Superfine: Tailoring Black Style” — a celebration of Black dandyism and style through the ages — it’s the perfect moment to honor the foundational fashion legacies born in Africa’s pre-colonial past. These styles weren’t just clothes. They were cultural markers. They were power in motion.

Style as Identity: Culture Woven Into Every Stitch

Across the continent, clothing spoke volumes. It revealed a man’s roots, his rank, his journey. Each region shaped its own sartorial language — tailored to climate, ceremony, and community values.

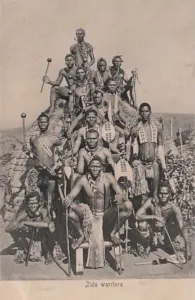

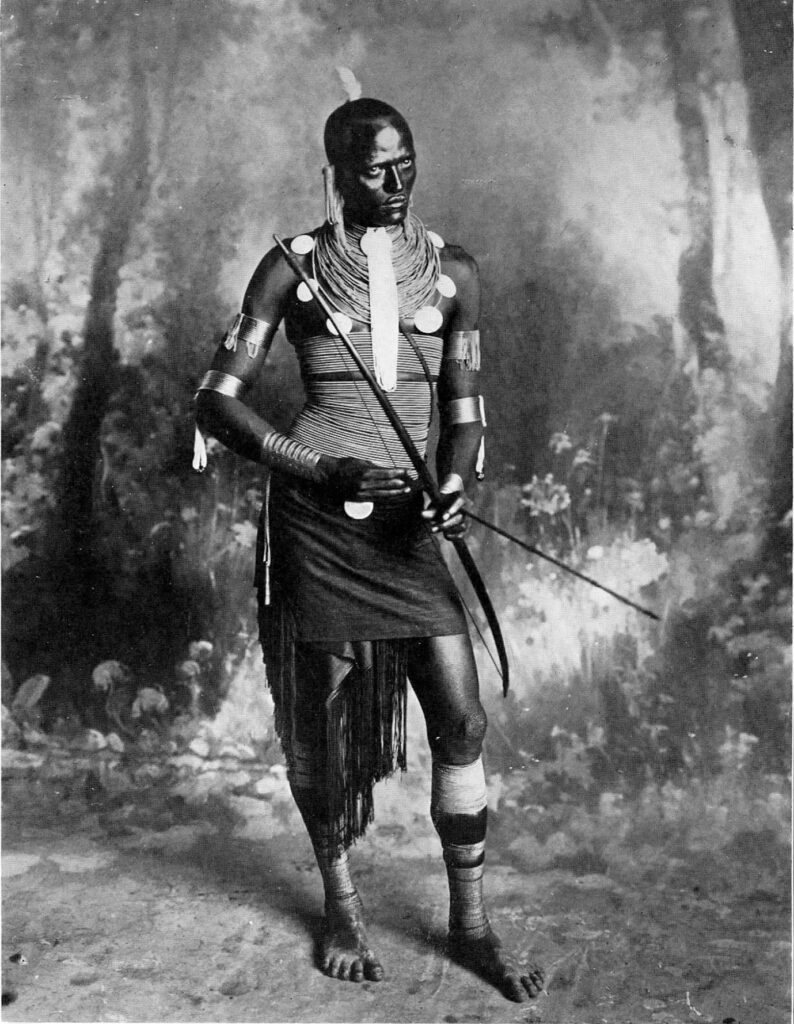

Among the Zulu of Southern Africa, men wore cowhide skirts and leather garments — durable, functional, and symbolic of strength. Beaded belts and necklaces weren’t mere adornment; they marked achievements and roles within society.

In West Africa, the Yoruba and Igbo traditions centered on wrapper cloths — wide, flowing fabrics often paired with the fila cap. These garments were made from rich textiles like Aso-Oke and Adire, their patterns and dyes representing lineage, artistry, and local pride.

Like today’s Black dandies, who blend style with resistance and joy, pre-colonial men dressed not only to be seen — but to be known.

Textiles of the Land: Materials that Mattered

Fashion was sustainable long before it was a trend. Pre-colonial African attire was crafted from natural, local materials — cotton, silk, bark cloth, leather, beads — each selected with purpose, each made with skill.

In the Mali Empire, men wore flowing indigo-dyed cotton robes, the depth of color and finesse of weave speaking to their rank and social standing.

In the lush Congo Basin, bark cloth — made from the softened inner bark of trees — became breathable tunics and wraps, crafted by artisans who passed down techniques through generations.

This was fashion in harmony with the environment — a principle today’s African designers continue to champion.

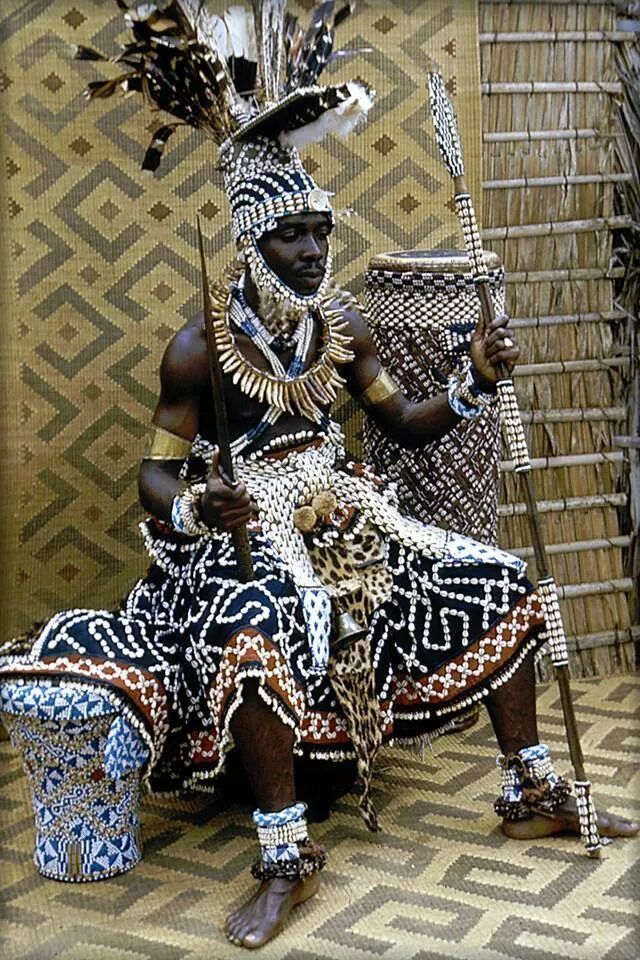

Power in Fabric: Clothing and Social Hierarchies

Attire served as a visual language of power, separating royalty from warriors, spiritual leaders from commoners. Garments didn’t just cover — they commanded.

Among the Ashanti of Ghana, kente cloth was the regalia of royalty. Woven by hand, each color and pattern carried meaning: gold for wealth, blue for peace, green for renewal. To wear kente was to wear a story.

In East Africa, the Maasai draped themselves in bold red shuka cloths, signaling unity, fearlessness, and warrior pride.

Across kingdoms and communities, fashion was authority in motion — much like today’s runway looks that reclaim luxury and leadership for the Black diaspora.

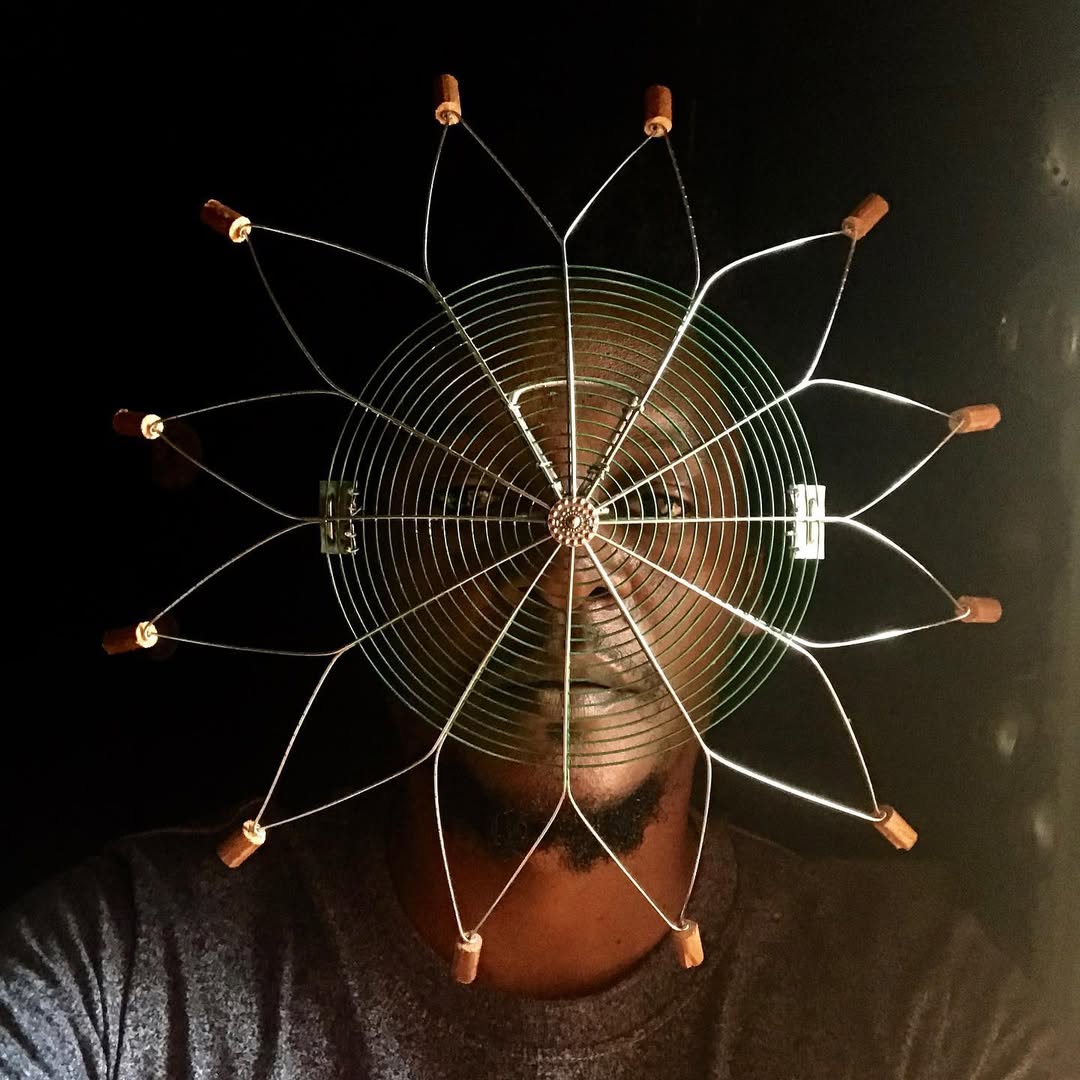

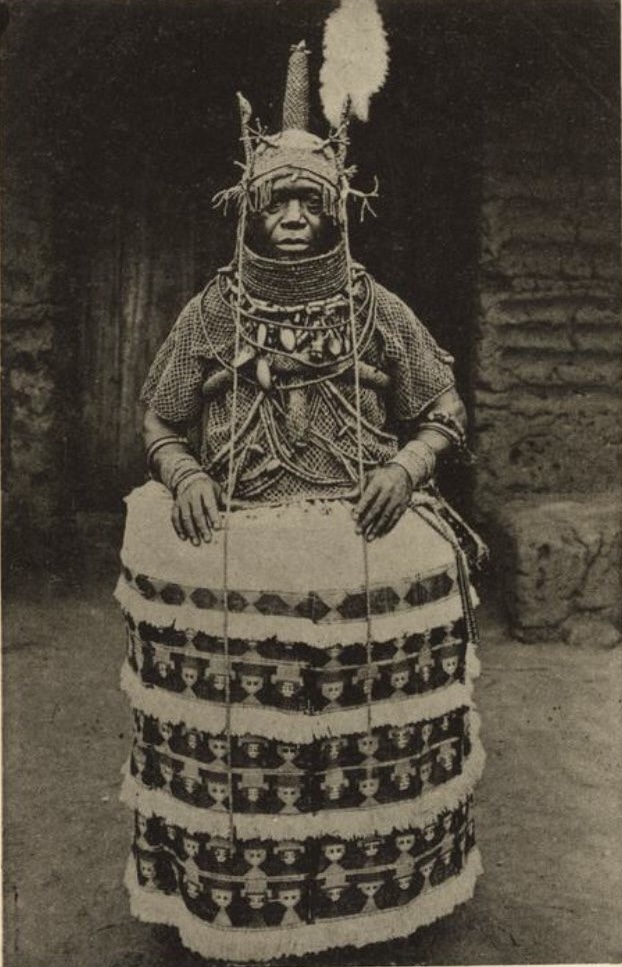

Ceremony and Spirit: Dressing for the Sacred

In moments of celebration, mourning, or transformation, pre-colonial clothing became deeply spiritual. Specific garments and adornments were worn only during rites of passage, rituals, and communal gatherings.

The Himba men of Namibia covered their skin in red ochre paste, both as sun protection and cultural expression — a marker of identity and maturity.

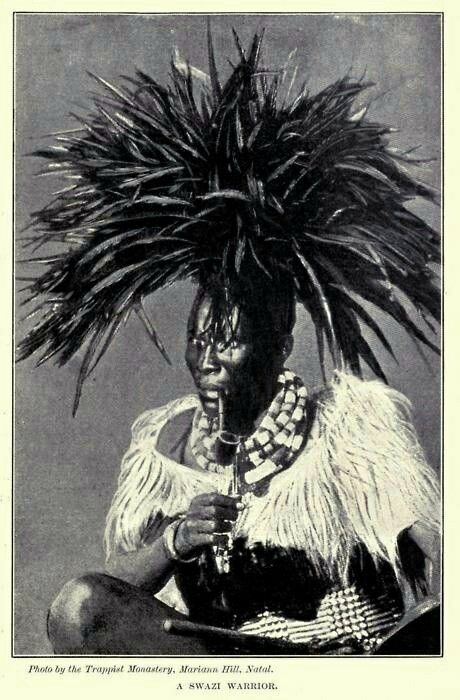

Zulu warriors donned feathered headdresses and animal hides for ceremonial dances, honoring their roles as protectors and leaders.

These were not costumes. They were sacred armor — woven with ancestral pride, passed down with reverence.

Function Meets Form: Practical Elegance

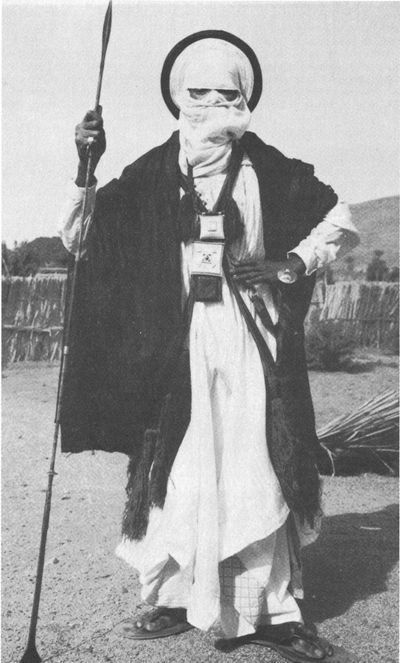

Pre-colonial fashion was as practical as it was expressive. Garments were designed to adapt to environment and lifestyle — whether in the desert, savannah, or rainforest.

In the Sahel, Fulani herders wore loose, breathable robes to combat heat and dust.

In the Congo’s dense forests, Mbuti hunter-gatherers wore minimal, flexible garments to move easily through thick vegetation.

Animal hides and fur were used to create protective gear for hunters navigating rugged terrain.

These looks were engineered for survival — without ever sacrificing style or meaning. A blend of elegance and utility that mirrors the ethos of modern Afro-futurist and streetwear fashion.

Legacy in Every Thread

Africa’s pre-colonial menswear was never just about covering the body. It was a living canvas of culture, identity, and ingenuity — woven with stories, dyed with meaning, and worn with purpose.

As the Met Gala celebrates the lineage of Black fashion, we’re reminded that the dapper silhouettes and refined tailoring we see today are built on generations of craft and creativity. Long before the spotlight, there was the sun-baked earth, the rhythm of the loom, and the pride of a man dressing in honor of who he was — and who he represented.

This is the legacy. This is the style. And it’s still alive, still evolving, still inspiring.