From the 1950s to the 1980s, as Africa waged its fight for independence and self-definition, a quiet revolution unfolded—one captured through the eyes of African women behind the lens. Defying colonial legacies and patriarchal gatekeeping, they reclaimed photography and film as instruments of power. Thérèse Sita-Bella, Felicia Ewurasi Abban, Safi Faye, Awa Tounkara, Ifeoma Onyefulu, Chantal Lawson, Mlle N’kegbe, Fanta Régina Nacro, and Mabel Cetu—these were women who dared to frame their world on their own terms.

Across three pivotal decades, they chronicled a continent in transformation. Their images spoke of pride, resilience, and humanity, countering the external gaze that sought to define Africa from the outside. In this Women’s Day feature for Guzangs, we honor these image makers—pioneers whose groundbreaking work laid the foundation for a new visual language, one that continues to inspire generations of African women behind the camera.

With the fall of colonial rule, photography evolved from a tool of oppression to a means of self-articulation. Yet, the industry remained a male stronghold, with women largely excluded from professional training, resources, and recognition. These Black female pioneers shattered those barriers. They turned studios, streets, and screens into arenas of resistance, capturing the pulse of their nations through portraiture, photojournalism, and film. From the turbulence of independence movements to the triumphs of cultural renaissance, their images did more than document history—they shaped its perception.

Born in 1933 among the Beti people of southern Cameroon, Thérèse Sita-Bella was a polymath—journalist, filmmaker, and pilot—who forged her own path in a landscape where women were rarely seen in media. Educated in Yaoundé and later in Paris, she trained at the Société de Radiodiffusion de la France d’Outre-Mer (SORAFOM). In 1963, she directed Tam-Tam à Paris, a groundbreaking documentary on Cameroonian culture—often cited as sub-Saharan Africa’s first film by a woman. Her bold cinematic vision paved the way for future generations, challenging global perceptions of Black life.

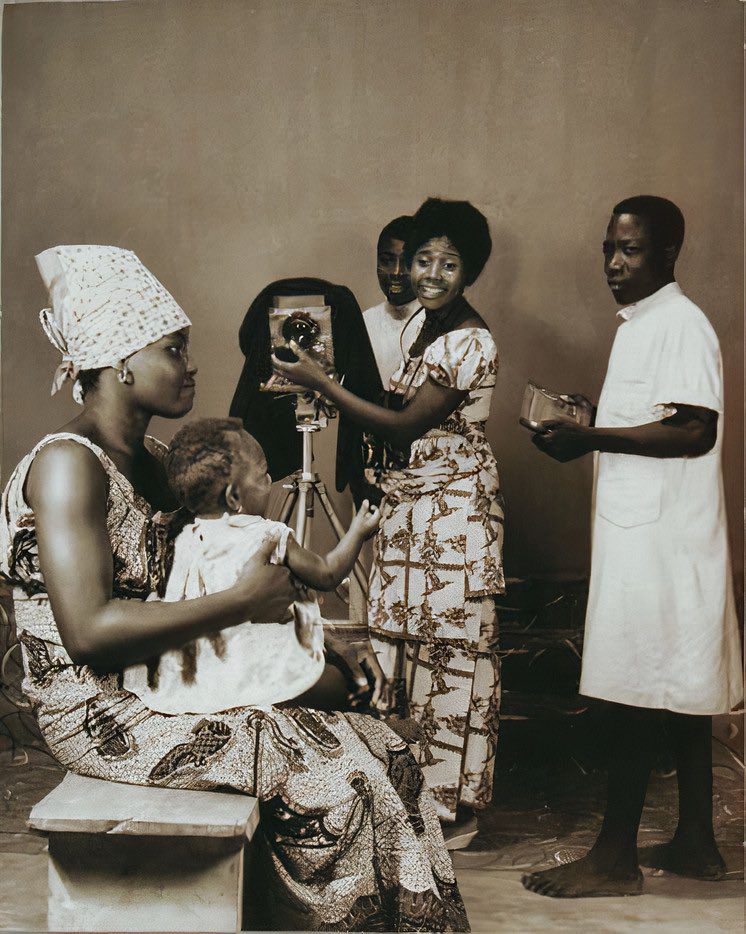

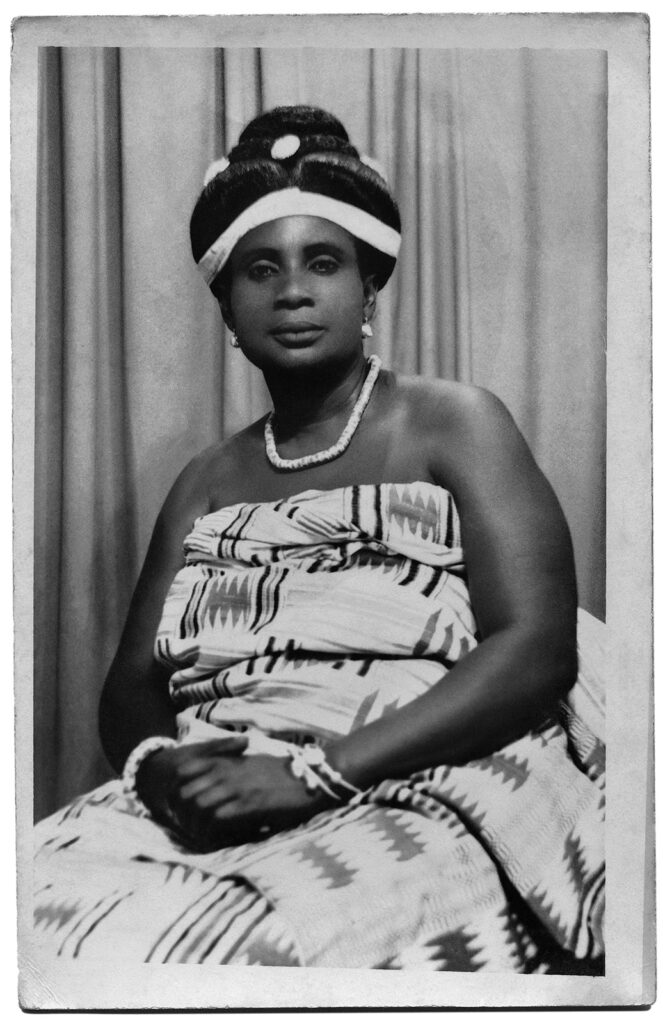

Felicia Ewurasi Abban began her journey in Ghana’s Western Region, apprenticing under her father at just 14. By 1953, she had established Mrs. Felicia Abban’s Day and Night Quality Art Studio in Accra’s Jamestown. Her portraits captured the essence of a newly independent Ghana—elegant, self-assured, in full ownership of its image. As Kwame Nkrumah’s official photographer in the 1960s, her work became a symbol of national pride, reframing the aesthetics of modern African identity.

Safi Faye, a teacher-turned-filmmaker, carved her legacy through a lens that merged documentary and fiction. Her debut feature Kaddu Beykat (1975), the first commercially distributed film by an African woman, shed light on the struggles of rural Senegalese farmers. With Fad’jal (1979), she deepened her commitment to centering Black women’s narratives. Faye’s films were not just stories—they were testimonies, reclaiming African voices long dismissed in global cinema.

Senegal’s first Black female photojournalist, Awa Tounkara, spent nearly four decades chronicling her country’s evolution. As a staff photographer for Le Soleil, she documented pivotal moments in Senegalese history—political shifts, cultural milestones, and the unfiltered realities of daily life. Named one of the world’s top 100 women reporters-photographers in 2021, her influence extended beyond her own work, mentoring the next generation of African photographers.

Little is known about Chantal Lawson and Mlle N’kegbe, yet their contributions are undeniable. Active in the 1960s and ‘70s, they were among Togo’s earliest professional women photographers. Lawson’s studio work, captured in a rare 1968 photograph by Evelyn Bernheim, marked a shift in how Black women documented themselves. Meanwhile, N’kegbe, trained in Lagos, worked for the Togolese Information Service, her images appearing in Amina Magazine. Though historical records on them remain scarce, their impact lingers in Togo’s visual history.

Fanta Régina Nacro reshaped Burkina Faso’s film industry, becoming the first Black woman from her country to direct a feature-length film. La Nuit de la Vérité (2004) and earlier works like Bintou (2001) offered raw, unfiltered narratives on gender and power. Her films rejected Western cinematic tropes, reclaiming African storytelling traditions and inspiring a new wave of Black women filmmakers.

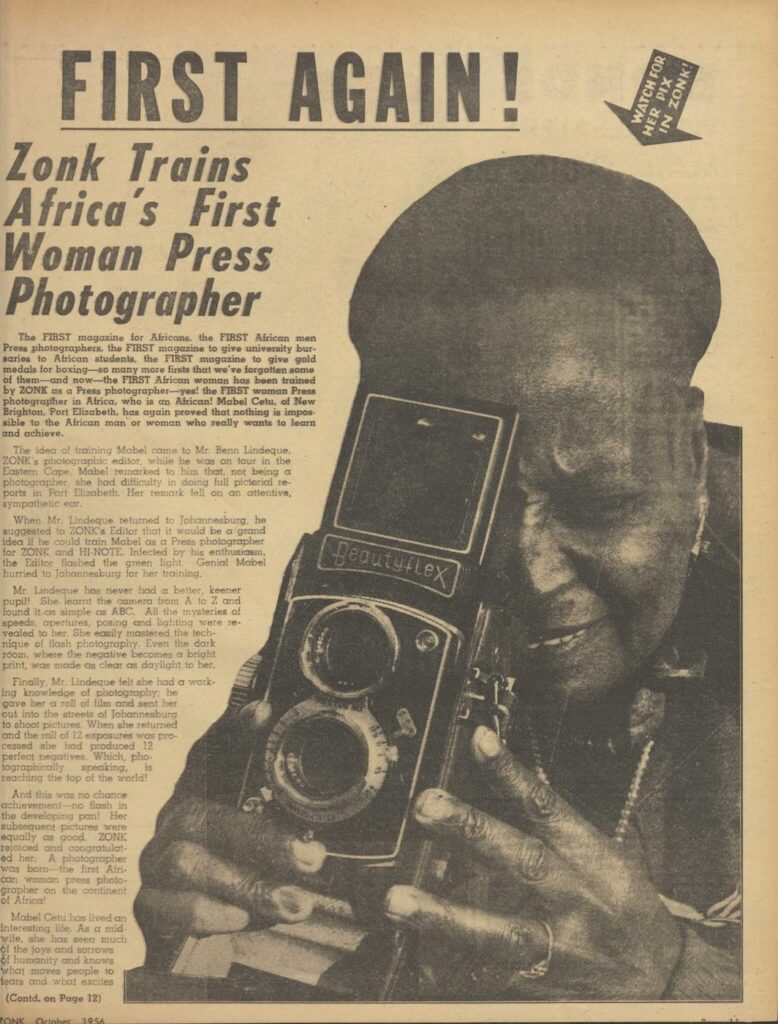

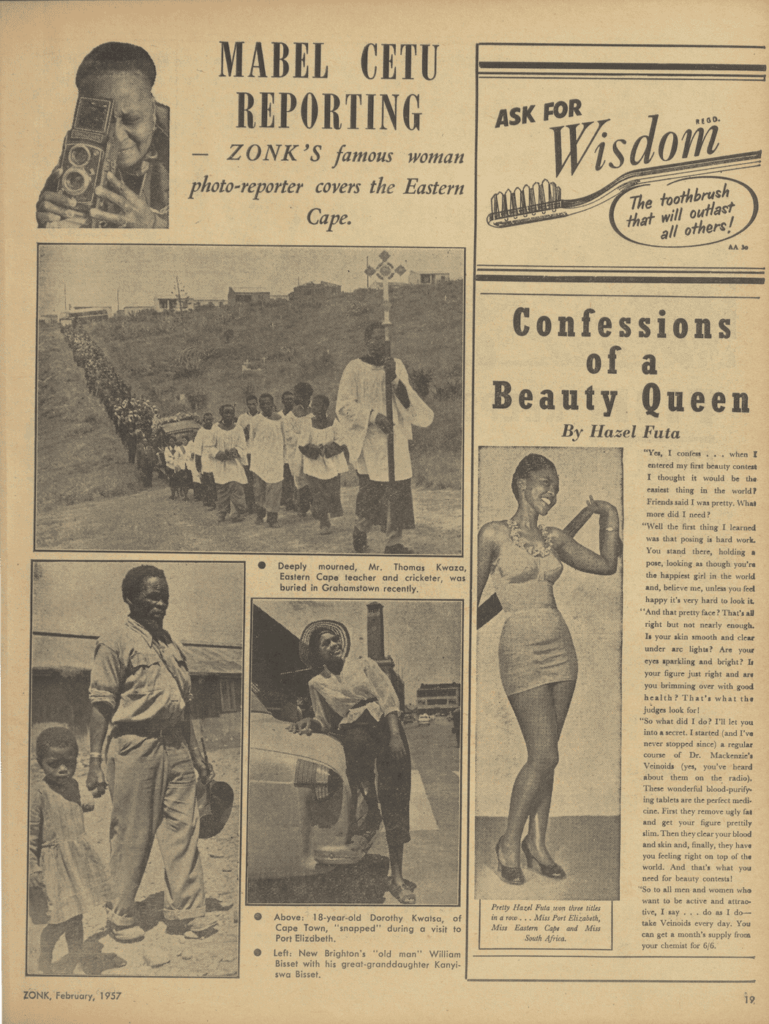

Mabel Cetu, known as Sis May, was South Africa’s first Black woman photojournalist. A nurse, broadcaster, and later a councilor, she worked for Zonk! magazine in the 1950s, capturing everyday life under apartheid. Much of her work has been lost or uncredited—a fate all too common for Black women artists of her era. Yet, her role in documenting resistance and survival remains a crucial part of South Africa’s photographic history.

A trained photographer and author, Ifeoma Onyefulu disrupted the one-dimensional portrayals of African life in global media. Her work in the 1980s, including A Is for Africa (1993), redefined how Nigerian village life was seen—intimate, nuanced, and deeply human. Her storytelling continues to influence young African visual artists seeking to reclaim their narratives.

From the 1930s to the late 20th century, these women transformed the act of photography and filmmaking into a means of resistance. With limited access to training and resources, they defied expectations—creating images that preserved Africa’s history through an intimate, self-defined lens.

Their influence is undeniable. Zanele Muholi’s radical portraiture, Aïda Muluneh’s bold visual language, and Fatoumata Diabaté’s cinematic compositions all trace back to the foundations these pioneers laid. Their work serves as a call to action—an insistence that Black women’s perspectives must not only be seen but centered.

As Guzangs celebrates these trailblazers, their legacy reminds us: they didn’t just document Africa—they shaped how Africa sees itself. In an era where the politics of representation remain urgent, their images endure as testaments of power, memory, and self-determination.

Editor’s Book References: